Abstract

In this Review, we describe the singular success of attractor neural network models in describing how the brain maintains persistent activity states for working memory, corrects errors and integrates noisy cues. We consider the mechanisms by which simple and forgetful units can organize to collectively generate dynamics on the long timescales required for such computations.

We discuss the myriad potential uses of attractor dynamics for computation in the brain, and showcase notable examples of brain systems in which inherently low-dimensional continuous-attractor dynamics have been concretely and rigorously identified. Thus, it is now possible to conclusively state that the brain constructs and uses such systems for computation.

Finally, we highlight recent theoretical advances in understanding how the fundamental trade-offs between robustness and capacity and between structure and flexibility can be overcome by reusing and recombining the same set of modular attractors for multiple functions, so they together produce representations that are structurally constrained and robust but exhibit high capacity and are flexible.

在这篇综述中, 我们描述了吸引子神经网络模型在描述大脑如何维持工作记忆的持续活动状态、纠正错误和积分噪声线索方面的独特成功. 我们考虑了简单且易忘的单元如何组织起来, 共同生成所需的长时间尺度动力学机制, 以进行此类计算.

我们讨论了吸引子动力学在大脑计算中的无数潜在用途, 并展示了在其中固有的低维连续吸引子动力学已被具体且严格识别的显著大脑系统示例. 因此, 现在可以明确地说, 大脑构建并使用这样的系统进行计算.

最后, 我们强调了最近在理解稳健性与容量之间以及结构与灵活性之间的基本权衡方面的理论进展, 这些进展可以通过重复使用和重新组合同一组模块化吸引子来克服, 从而共同产生结构受限且稳健但具有高容量且灵活的表示.

Introduction

One of biology’s grand challenges is to explain how order and complex function spring from inanimate physical systems composed of much simpler parts. The brain creates order in its representations of the world and performs complex functions through the collective interactions of simpler elements.

In this Review, we describe and evaluate the hypothesis that attractor dynamics in widespread regions of the CNS have a key role in constructing some of these representations, generating long timescales to support integration and memory functions and endowing all these functions with robustness.

We review the specific predictions of attractor-based models and the now extensive body of work testing these predictions. Thus, we illustrate that the theory and validation of computation with attractor dynamics in the brain is one of the biggest success stories in systems neuroscience.

生物学的一个重大挑战是解释无生命的物理系统如何从更简单的部分中产生秩序和复杂功能. 大脑通过更简单元素的集体相互作用, 在其对世界的表征中创造秩序并执行复杂功能.

在这篇综述中, 我们描述并评估了这样一个假设: 中枢神经系统 (CNS) 广泛区域中的吸引子动力学在构建这些表征、生成支持整合和记忆功能的长时间尺度以及赋予所有这些功能以稳健性方面起着关键作用.

我们回顾了基于吸引子的模型的具体预测以及现在广泛的工作来测试这些预测. 因此, 我们说明了在大脑中使用吸引子动力学进行计算的理论和验证是系统神经科学中最大的成功故事之一.

Some of the first formal circuit-level models of brain function focused on the problem of associative memory and how neural circuits might generate spatially distributed, stable patterns of activity that could function as such a memory.

Hopfield networks, with multiple stable states constructed by inscribing input patterns into connection weights, were proposed more than four decades ago.

Network models possessing a continuous set of stable states that could be used to represent continuous variables were also first proposed in the same period. Subsequently, many canonical brain circuits for motor control, sensory amplification and memory, motion integration, evidence integration, decision-making and spatial navigation have been modelled using the same general principle — that a set of states can be stabilized through collective positive feedback.

一些最早的正式回路级大脑功能模型集中在 联想记忆 的问题上, 以及神经回路如何产生空间分布的稳定活动模式, 这些模式可以作为这样的记忆.

Hopfield 网络通过将输入模式 铭刻 到连接权重中, 构建了多个稳定状态, 这一概念在四十多年前就被提出了.

具有一组连续稳定状态的网络模型也首次在同一时期被提出, 这些状态可用于表示连续变量. 随后, 许多用于运动控制、感觉放大和记忆、运动积分、证据积分、决策和空间导航的典型大脑回路都使用了相同的一般原理进行建模——即通过集群正反馈可以稳定一组状态.

Because these are circuit-level models, but were typically inspired by experimental characterization of neurons recorded singly or a few at a time, the patterns of connectivity and the cell-activity correlations in the models automatically became novel and relatively specific predictions about the population dynamics and architecture of such circuits.

As we discuss below, the combination of these prediction-rich (yet conceptually simple) models, modern experimental breakthroughs in the acquisition of cellular-resolution population activity data and novel and rigorous analyses of such data on the basis of the model predictions has provided much evidence that the brain constructs and exploits attractor networks for performing several essential computations.

由于这些是回路级模型, 但通常是受单独或少量记录的神经元的实验表征启发, 因此模型中的连接模式和细胞活动相关性自然而然成为关于此类回路的 群体动力学 和架构的新颖且相对具体的预测.

正如我们下面讨论的那样, 这些富有预测力 (但概念上简单) 模型的结合、在获取细胞分辨率群体活动数据方面的现代实验突破以及基于模型预测对这些数据进行的新颖且严格的分析, 提供了大量证据表明大脑构建并利用吸引子网络来执行几项基本计算.

We begin by defining attractors, and then describe proposed mechanisms for the construction of attractor network models in neuroscience. We provide an overview of why attractor networks can be important for computation in the brain and highlight criteria for determining whether a system has non-trivial attractor dynamics.

We also discuss examples of brain circuits with non-trivial attractor dynamics. We end with a summary of new directions in our understanding of how these simple circuits could contribute to flexible computation through reuse in multiple contexts.

我们首先定义吸引子, 然后描述神经科学中吸引子网络模型构建的假定机制. 我们概述了为什么吸引子网络对于大脑中的计算可能很重要, 并强调了确定系统是否具有非平凡吸引子动力学的标准.

我们还讨论了具有非平凡吸引子动力学的大脑回路示例. 最后, 我们总结了我们对这些简单回路如何通过在多种环境中重复使用来促进灵活计算的新理解方向.

What are attractors?

To define an attractor, we first define a dynamical system and its states.

A dynamical system is a set of variables together with all the rules that determine their changes in value with the passage of time.

The value of these variables at any given instant is called the state of the system at that moment. The state is a point (vector) in the state space of the dynamical system.

An attractor is the minimal set of states in a state space, to which all nearby states eventually flow with time. One simple example of an attractor is a stable fixed point: all neighbouring states flow to it.

Transferring these crisp mathematical definitions to the context of the brain involves challenges and simplifications that revolve around identifying a sufficiently self-contained system and the variables necessary to determine its dynamics.

为了定义吸引子, 我们首先定义一个动力系统及其状态.

动力系统是一组变量以及所有决定它们随时间变化的规则.

这些变量在任何给定时刻的值称为该时刻系统的状态. 状态是动力系统状态空间中的一个点 (矢量).

吸引子是状态空间中最小的状态集, 所有附近状态最终都会随着时间流向该状态集. 吸引子的一个简单例子是稳定的不动点: 所有邻近状态都流向它.

将这些清晰的数学定义转移到大脑的背景中涉及挑战和简化, 这些挑战和简化围绕识别一个 足够自包含的系统 以及确定其动力学所需的变量展开.

Defining the state of a neural system

Inherent in the definition of a dynamical system is the assumption that there are no external dynamical inputs to the system (or, equivalently, that the system definition includes all such external variables).

在动力系统的定义中, 固有地假设系统没有外部动力输入 (或者等效地, 系统定义包括所有此类外部变量).

The first simplification in characterizing the dynamics of a neural circuit is to assume that, at least on the timescale of interest, the system evolves in an autonomous way.

Given that subcircuits in the brain are interconnected with others, and that the brain itself interacts with the world, it is impossible to isolate these circuits completely into autonomous systems.

However, we may define a notion of ‘effectively autonomous’ dynamics, whereby inputs do not vary over time and are untuned, in the sense that they do not provide differential drive to subsets of the putative set of attractor states.

表征神经回路动力学的第一个简化是 假设至少在感兴趣的时间尺度上, 系统以 自主 的方式演化.

鉴于大脑中的子回路与其他回路相互连接, 并且大脑本身与世界互动, 因此不可能将这些回路完全隔离成自主系统.

然而, 我们可以定义 “等效自主” 动力学的概念, 即输入不随时间变化且未受调制, 从而不会为假定的吸引子状态集的子集提供差异驱动.

The second simplification is in defining the states of the system.

The changes in state of a circuit in the brain over time may depend on the detailed pattern of all the spikes in all neurons, the levels of associated ions, neurotransmitters and modulators, and even the states of the ion channels.

The weights and connections between neurons may be considered as parameters (rather than variables) on short timescales, but are themselves variables if considering a longer timescale.

One widely used simplification in describing a neural circuit on the timescale of seconds is to use just the spiking outputs of the neurons in the circuit as the states, often further simplified as time-varying spike rates.

If such a description is sufficient to predict the state changes of the system at the relevant timescales, it can be viewed as a reasonable dynamical system model of the circuit.

Although spike or spike-rate descriptions ignore subcellular and molecular variables to make the grossly simplifying assumption that the relevant circuit dynamics are governed by spikes, the state space of a vertebrate microcircuit described in this way is nevertheless very high-dimensional, comprising the number of neurons in the circuit, which can be in the order of $10^2-10^7$ cells.

As we discuss below, such simplified models can nevertheless yield rich and accurate predictions about neural circuits.

第二个简化是在定义系统状态时.

大脑中回路随时间变化的状态变化可能取决于所有神经元中所有脉冲的详细模式、相关离子、神经递质 和 调节剂 的水平, 甚至离子通道的状态.

在短时间尺度上, 神经元之间的权重和连接可以被视为参数 (而不是变量) , 但如果考虑更长的时间尺度, 它们本身就是变量.

在描述秒级时间尺度上的神经回路时, 一个广泛使用的简化是仅使用回路中神经元的 脉冲输出 作为状态, 通常进一步简化为含时脉冲率.

如果这样的描述足以预测相关时间尺度上系统的状态变化, 则可以将其视为回路的合理动力系统模型.

尽管脉冲或脉冲率表述忽略了亚细胞和分子变量, 以做出相关回路动力学由脉冲控制的粗略简化假设, 但以这种方式描述的 脊椎动物 微回路的状态空间仍然是非常高维的, 包括回路中的神经元数量, 可能在 $10^2-10^7$ 个细胞的范围内.

正如我们下面讨论的那样, 这样的简化模型仍然可以产生关于神经回路丰富且准确的预测.

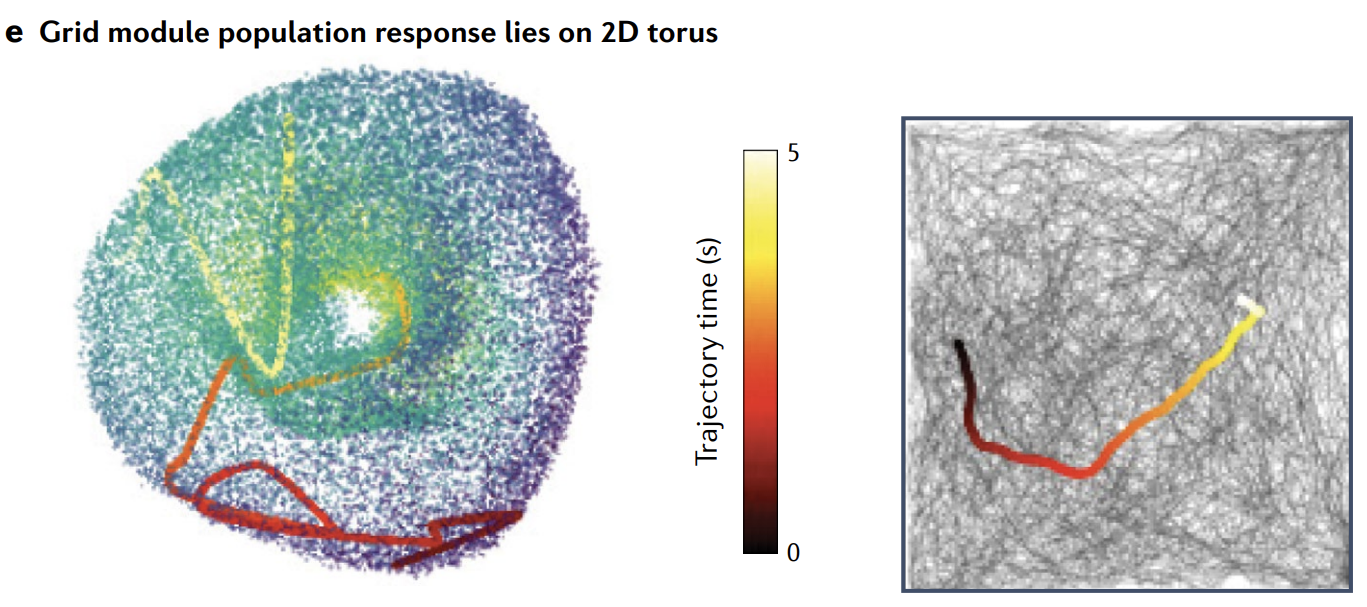

Attractors exist in various flavours: an attractor may consist of a single state, a set of discrete states, a set of states that effectively behave as a continuous set or many such near-continuous sets (Fig. 1).

If a set of attractor states traces out a shape in state space that is approximately continuous and locally Euclidean, it is known as an attractor manifold.

Nonlinear continuous-attractor manifolds can be curved and topologically complex (for example, resembling rings, tori and so on; Fig. 1c,d, rightmost column). States on an attractor may be stationary, or might flow along the attractor to trace out trajectories that are periodic (known as limit cycles; Fig. 1f, rightmost column) or chaotic (that is, with dynamics that are inherently unpredictable owing to high sensitivity to small changes in the state).

吸引子存在各种形式: 吸引子可以由单个状态、一组离散状态、一组有效地表现为连续集的状态或许多这样的近连续集组成 (图 1).

如果一组吸引子状态在状态空间中描绘出一个近似连续且局部欧式几何的形状, 则称其为 吸引子流形.

非线性连续吸引子流形可以是弯曲且拓扑复杂的 (例如, 类似于环、环面等; 图 1c、d, 最右列). 吸引子上的状态可以是静止的, 或者可能沿着吸引子流动以描绘出周期性轨迹 (称为 极限环; 图 1f, 最右列) 或 混沌 (即, 由于对状态微小变化的高度敏感性而具有固有不可预测性的动力学).

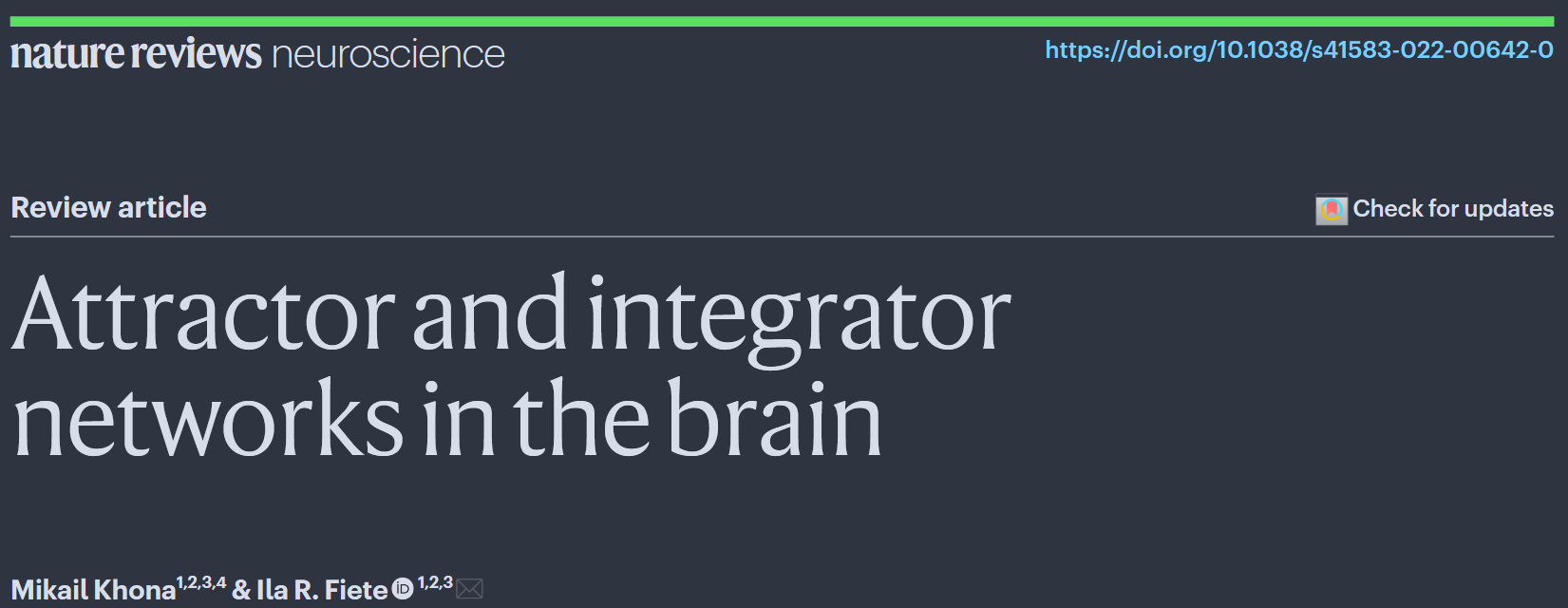

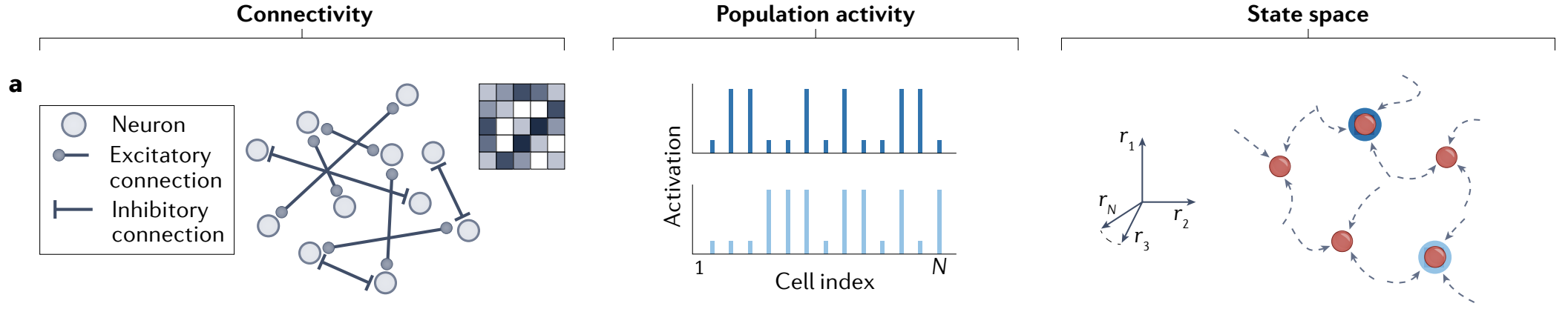

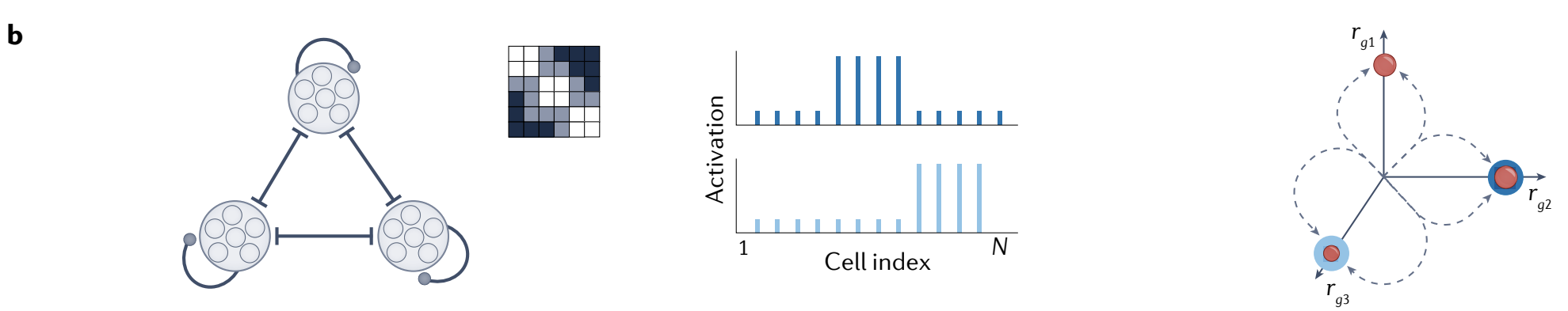

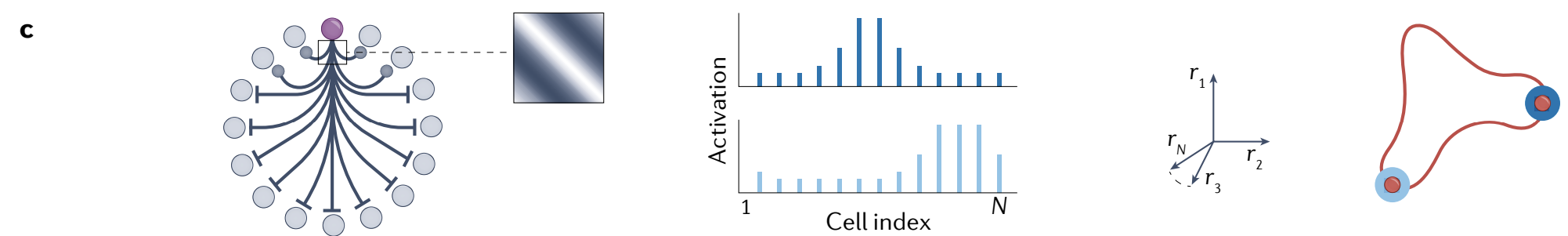

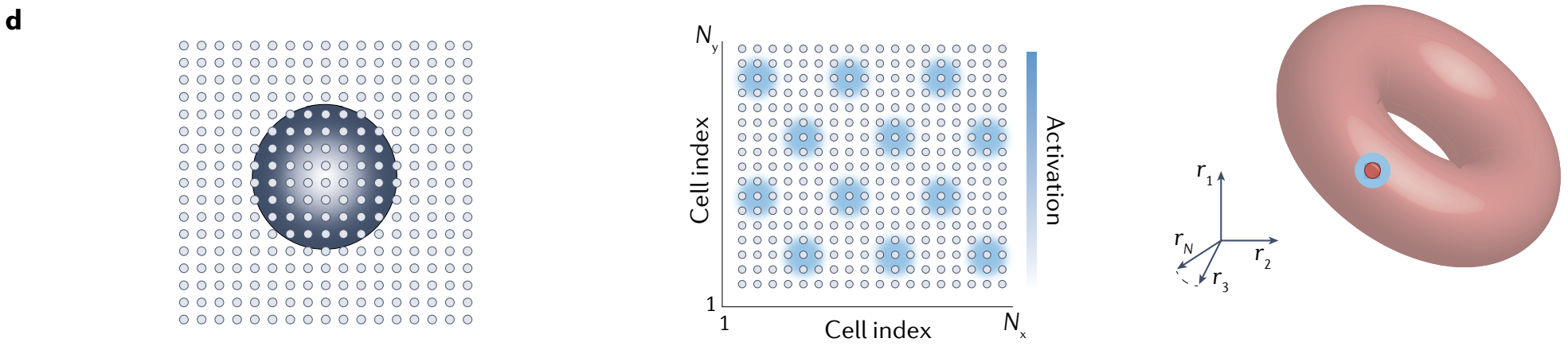

Fig. 1 | Mechanisms of attractor formation.

Left columns: open grey circles represent neurons, and connections between them are excitatory (black lines ending in bars) or inhibitory (black lines ending in circles). For layout of neurons and connections, connectivity matrices are shown as the inset, with black to white colours indicating strongly inhibitory to excitatory interactions, respectively.

Middle columns: examples of stable population activity patterns.

Right columns: state-space views of population states and dynamics. Red circles with shades of blue rings indicate the activity states shown in middle column; grey lines denote transient dynamic trajectories and red denotes attracting states.

图 1 | 吸引子形成机制.

左列: 开放的灰色圆圈代表神经元, 连接它们的是 兴奋性 (以棒结尾的黑线) 或 抑制性 (以圆圈结尾的黑线). 对于神经元和连接的布局, 插图中显示了连接矩阵, 黑色到白色表示强抑制到(强)兴奋性相互作用.

中间列: 稳定的群体活动模式示例.

右列: 群体状态和动力学的状态空间视图. 带有蓝色环阴影的红色圆圈表示中间列中显示的活动状态; 灰色线表示瞬态动态轨迹, 红色表示吸引状态.

a, A network with dense symmetric connections determined by associative Hebbian learning on a set of input patterns (middle) stores them as stable attractor states. This defines a Hopfield network.

a、由一组输入模式上的联想 Hebbian 学习确定的密集对称连接网络 (中间) 将它们存储为稳定的吸引子状态. 这定义了 Hopfield 网络.

b, Disjoint groups of neurons that interact through within-group excitation and across-group inhibition lead to group winner-takes-all (WTA) dynamics. Stable states are any patterns with one winning group. The state-space plot collapses all activities of neurons in group $g_{i}$ along the axis $r_{gi}$.

b、通过 组内兴奋 和 组间抑制 相互作用的不相交神经元组导致组赢家通吃 (WTA) 动力学. 稳定状态是具有一个获胜组的任何模式. 状态空间图沿轴 $r_{g_{i}}$ 折叠了组 $g_{i}$ 中神经元的所有活动.

c, Neurons arranged in a ring with global inhibition and either local excitation or a lack of local inhibition, combined with uniform excitatory input to all neurons, produce localized activity bumps (middle) as the stable states.

Bumps may be centred anywhere on the neural ring, defining a near-continuum of attractor states that form a ring in state space (right).

c、在环上排列的神经元具有 全局抑制 和 局部兴奋 或 局部抑制缺乏, 结合对所有神经元的均匀兴奋输入, 产生局部活动峰值 (中间) 作为稳定状态.

峰值可以位于神经环上的任何位置, 在状态空间中定义了一个近连续的吸引子状态环 (右).

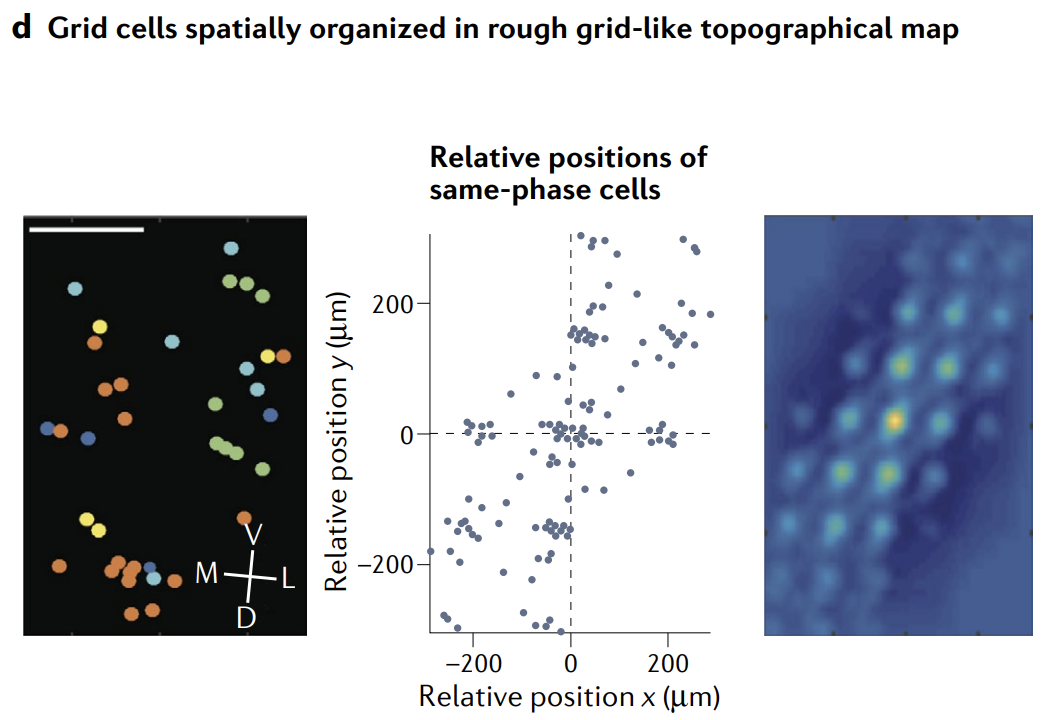

d, Neurons arranged on a two-dimensional neural sheet, interacting through local inhibition and either centre excitation or a lack of inhibition near the centre with uniform excitatory input to all neurons, result in a pattern of multiple periodically spaced activity bumps (middle).

Any two-dimensional phase shift of the periodic pattern up to the lattice periodicity results in distinct but equivalent stable states, and then the states repeat; thus, the result is a torus of stable states.

d、在二维神经片上排列的神经元通过 局部抑制 相互作用, 并且在中心附近具有 中心兴奋 或 抑制缺乏, 对所有神经元进行均匀兴奋输入, 导致多个周期性间隔活动峰值的模式 (中间).

周期性模式的任何(晶格周期性的)二维相移都会导致不同但等效的稳定状态, 然后状态重复; 因此, 结果是一个稳定状态环面.

圆环和圆环的直积形成环面(torus), 即 $S^{1}\otimes S^{1} = T^{2}$

用到的连接方式被比喻为 Mexican-hat.

e, Two neuron groups with in-group excitation and across-group inhibition, precisely tuned interaction strengths and quasi-linear neural input-output responses can counteract activity decay in the network and produce persistent activity over a continuum of activity levels in the two populations, defining ramp-like neural tuning and a line of attractor states.

e、两个具有 组内兴奋 和 组间抑制、精确调制相互作用强度和准线性神经输入-输出响应的神经元组可以抵消网络中的活动衰减, 并在两个群体中产生连续的活动水平上的持续活动, 定义了阶梯状神经调制和一系列吸引子状态.

f, Neurons arranged on a ring with asymmetric connections drive a flow of neural activity in a particular direction.

The network forms localized activity bumps that sequentially move around the ring in that direction (middle). The state space contains a limit-cycle attractor (right).

f、在环上排列的神经元具有不对称连接, 驱动神经活动朝特定方向流动.

网络形成局部活动峰值, 依次围绕该环移动 (中间). 状态空间包含一个 极限环吸引子 (右).

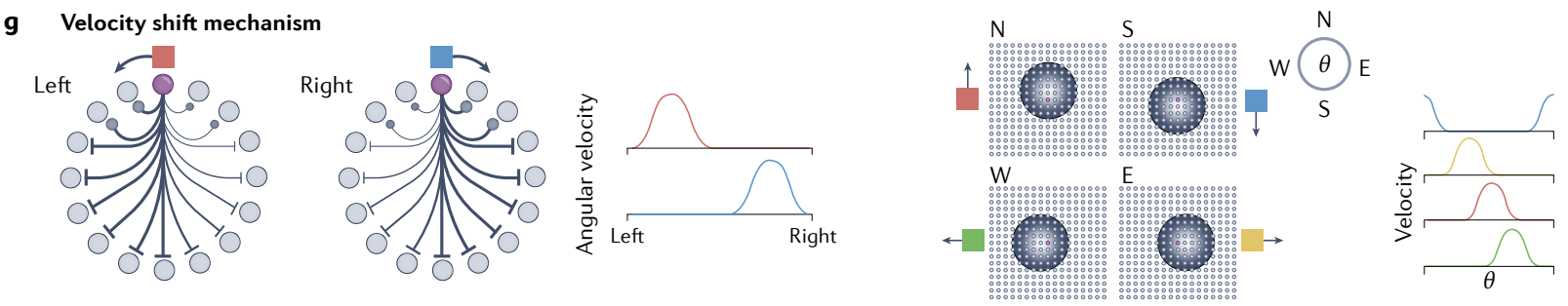

g, The copy-and-offset mechanism for constructing integrators, illustrated for the ring (left) and grid (right) attractor circuits. Each network copy receives velocity inputs tuned to the corresponding shift direction.

g、构建积分器的 复制和偏移机制, 说明了环 (左) 和网格 (右) 吸引子回路. 每个网络副本接收调制于相应偏移方向的速度输入.

Various combinations of such attractors, of different dimensions, geometries and topologies, may coexist in different regions of the state space of a single dynamical system.

Typically, the set of attractors in a dynamical system comprises a small subset of the state space, and attractor manifolds are usually much lower-dimensional than the state space.

In cases in which a system has multiple attractor states, the initial condition determines the attractor state to which the system flows.

各种不同维度、几何形状和拓扑结构的吸引子组合可能共存于单一动力系统状态空间的不同区域中.

通常, 动力系统中的吸引子集合构成状态空间的一个小子集, 并且吸引子流形通常比状态空间维数低得多.

若系统具有多个吸引子状态, 初始条件决定了系统流向的吸引子状态.

Attractors in the presence of noise

Any real physical system unavoidably behaves non-deterministically from the perspective of a model of the system.

This is because one cannot observe and describe all variables, and all uncharacterized variables together with true stochastic sources of variation (such as synaptic signalling noise from stochastic vesicle release; fluctuations in ion concentrations during processes such as spike initiation and calcium signalling; or fluctuations in small copy numbers of proteins) serve as effective sources of noise in the model.

Noise can disrupt states so they do not strictly localize to the attractor described in a noise-free version of the model, and can drive the system to escape from an attractor over time.

However, the general idea of attractor states remains, in that, if the system is initialized near such a state, it tends to flow towards it and subsequently remains localized around it, for extended periods.

从系统模型的角度来看, 任何真实的物理系统不可避免地表现出不确定性.

这是因为无法观察和描述所有变量, 所有未表征的变量以及真正的随机变化源共同作为模型中的等效噪声源 (例如来自随机囊泡释放的 突触信号噪声; 在尖峰启动和钙信号等过程中离子浓度的波动; 或蛋白质的小拷贝数波动).

噪声可能会干扰状态, 因此(状态)不会严格 定域 到无噪声模型中描述的吸引子, 且随着时间的推移, 噪声可能驱动系统逃离吸引子.

然而, 广义的吸引子状态概念仍然存在, 即如果系统初态在这样的状态附近, 它倾向于流向它并随后长时间保持在其周围.

Because attractor states are where systems tend to localize (when not externally driven), they should be observable in the autonomous dynamics of real systems.

This basic property is the basis for the most fundamental and robust tests of attractor dynamics in neural systems, as we discuss below.

In a nutshell, the central signatures of attractors in real systems (discussed in more detail in later sections of this Review) can be summarized as: the localization of the states of a system to a lower-dimensional subset; the flow of the states towards the subset after perturbation; and the long-time and (effectively) autonomous stability of states in that subset.

由于吸引子状态是系统 (没有外部驱动时) 倾向于定域的地方, 因此它们应该可以在真实系统的自主动力学中观察到.

这一基本属性是神经系统中吸引子动力学最基本和最稳健测试的基础, 正如我们下面讨论的那样.

简而言之, 真实系统中吸引子的中心特征 (在本综述的后续部分中将更详细地讨论) 可以总结为: 系统状态定域至低维子集; 微扰后状态流向该子集; 以及该子集中状态的长期和 (有效地) 自主稳定性.

Construction and mechanisms

The general principle underlying the formation of non-trivial attractor states in neural circuits is strong recurrent positive feedback. Positive feedback fights activity decay to stabilize certain states, and has been posited to be the basis for the stabilization of memory traces and persistent activity in the brain.

Which states become stabilized into attractors depends on how the network sculpts the positive feedback, which, according to the synaptic hypothesis, is determined by synaptic weights.

在神经回路中形成非平凡吸引子状态的基本原理是 强烈的递归正反馈. 正反馈抵抗激活衰减以稳定某些状态, 这被假定为大脑中记忆痕迹和持续激活稳定化的基础.

根据突触假说, “何种状态被稳定为吸引子” 取决于 “网络如何塑造正反馈”, 需要被突触权重决定.

In general, characterizing the relationship between structure and function in a large collection of interacting elements is extremely difficult.

For example, a large collection of simple polar three-atom molecules of hydrogen and oxygen give rise to the emergent phenomena we associate with water — such as liquidness, wetness and freezing into a solid — that cannot be predicted through intuition or by drawing box and arrow diagrams.

Nevertheless, the transitions and properties of emergent states can be described relatively simply, with very few key parameters and variables.

一般来说, 表征大量相互作用元素之间的结构与功能关系是非常困难的.

例如, 大量由氢和氧组成的简单极性三原子分子产生了我们与水相关的 涌现现象——比如液态、湿润和冻结成固体——这些现象无法通过直觉或绘制框图和箭头图来预测.

然而, 涌现状态 的转变和属性可以相对简单地描述, 只需很少的关键参数和变量.

One way to characterize the relationship between synaptic weights and attractor dynamics is to ask what attractor states a given set of weights produces (the ‘forward’ problem).

With a given set of weights, one can simulate a circuit and explore the resulting dynamics to find attractors of the system. A more powerful method, the Lyapunov function approach, holds for symmetric weight matrices ($W_{ij} = W_{ji}$) and ratebased neural dynamics.

For this class of models, a generalized energy function (the Lyapunov function), which is a function of the weights and neural activation function, analytically specifies the network’s dynamics.

Stable and unstable attractor states are the energy minima and maxima of the derived landscape, respectively, and the network’s state flows downhill towards the attractors (Fig. 2e) in the way a ball rolls down a gravitational potential.

表征突触权重与吸引子动力学之间关系的一种方法是询问给定权重集产生了哪些吸引子状态 ( “正向” 问题).

通过给定一组权重, 可以模拟回路并探索由此产生的动力学以找到系统的吸引子. 更强大的方法是 Lyapunov 函数方法, 它适用于对称权重矩阵 ($W_{ij} = W_{ji}$) 和基于速率的神经动力学.

对于这一类模型, 广义能量函数 (Lyapunov 函数) , 它是权重和神经激活函数的函数, 解析地指定了网络的动力学.

稳定和不稳定的吸引子状态分别是导出景观的能量极小值和极大值, 网络的状态沿着吸引子向下流动 (图 2e) , 就像球沿着引力势滚动一样.

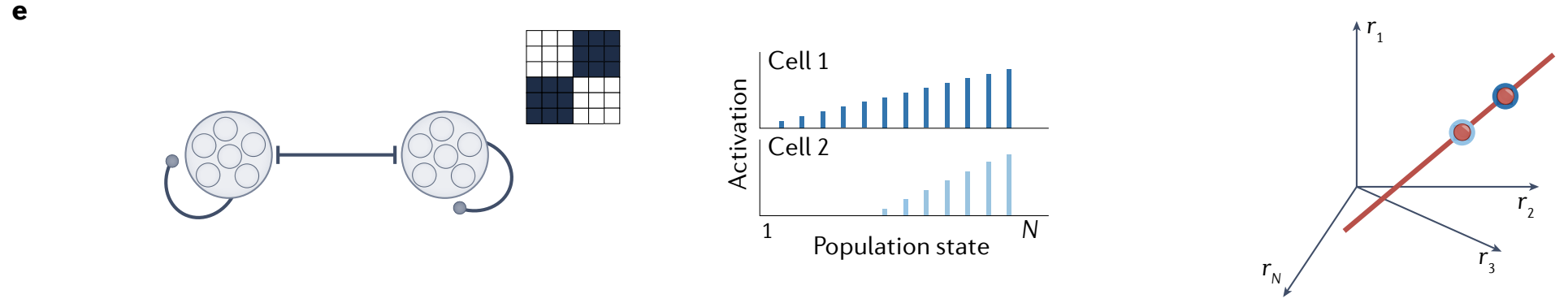

Fig. 2 | The utility of low-dimensional attractor networks.

图 2 | 低维吸引子网络的实用性.

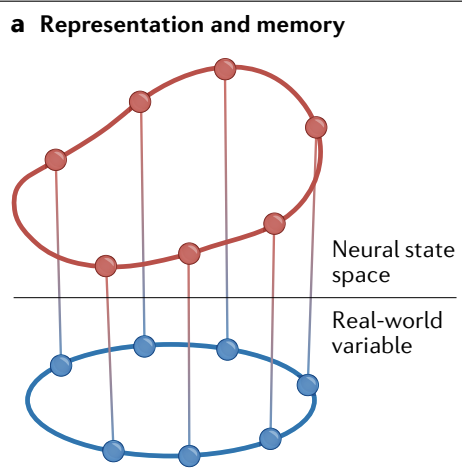

a, Persistent and stable states generated by attractor networks (red) can be used to represent and remember external variables (blue) by constructing an appropriate mapping between them (vertical lines).

a、 吸引子网络 (红色) 产生的持续且稳定的状态可以通过在它们之间构建适当的映射 (垂直线) 来表示和记忆外部变量 (蓝色).

b, Attractor networks can correct errors by mapping noisy states to the nearest attractor state.

$N$-dimensional noise drawn from the unit sphere centred on a one-dimensional attractor has a projection strength of only $1/N$ along the attractor: in this counter-intuitive high-dimensional geometry, a ball is more similar to a pancake, with the attractor orthogonal to the large dimensions.

b、吸引子网络可以通过将 受噪状态 映射到最近的吸引子状态来纠正错误.

从以一维吸引子为中心的单位球中绘制的 $N$ 维噪声在吸引子上的投影强度仅为 $1/N$: 在这种违反直觉的高维几何中, 球更类似于煎饼, 吸引子与大维度正交.

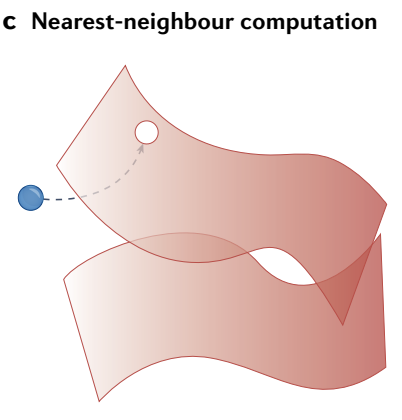

c, Flow to the nearest (continuous or discrete) attractor can perform a nearest-neighbour computation and, thus, perform classification. For example, the two attractors may represent ‘cat’ and ‘dog’ perceptual manifolds, and the blue dot a specific input data point.

c、流向最近的 (连续或离散) 吸引子可以执行 最近邻计算, 从而执行分类. 例如, 两个吸引子可能代表 “猫” 和 “狗” 的感知流形, 蓝点代表特定的输入数据点.

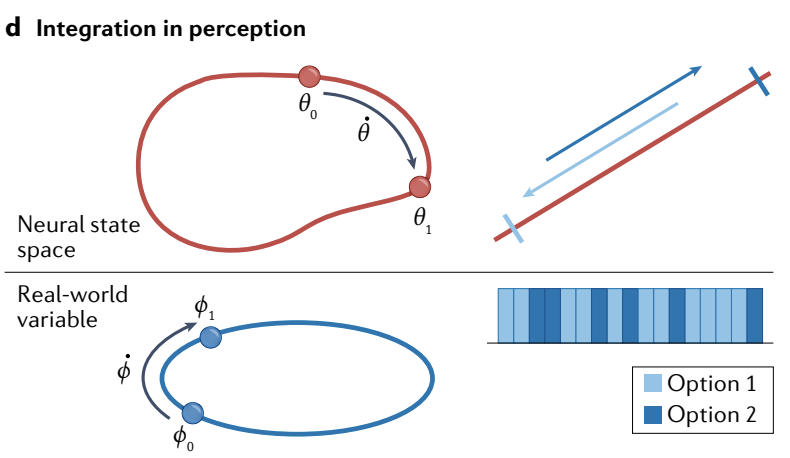

d, Left: continuous attractors can become integrators if velocities or movements in the external space are inputs to the network and induce proportional shifts in the internal attractor state. The current state on the attractor is then the integral of past velocity inputs relative to the starting state.

Right: if the input to an integrating attractor consists of temporally varying evidence pulses (bottom, evidence about one option in dark blue and evidence about the opposing option in light blue), these will move the state on the attractor (top) so the system’s current state reflects the integral of the total evidence.

d、左: 如果外部空间中的速度或运动是网络的输入并引起内部吸引子状态的成比例偏移, 则连续吸引子可以成为积分器. 那么, 吸引子上的当前状态是相对于起始状态的过去速度输入的积分.

右: 如果积分吸引子的输入由时间变化的 证据脉冲 组成 (底部, 深蓝色表示一个选项的证据, 浅蓝色表示相反选项的证据) , 这些将移动吸引子上的状态 (顶部) , 因此系统的当前状态反映了所有证据的积分.

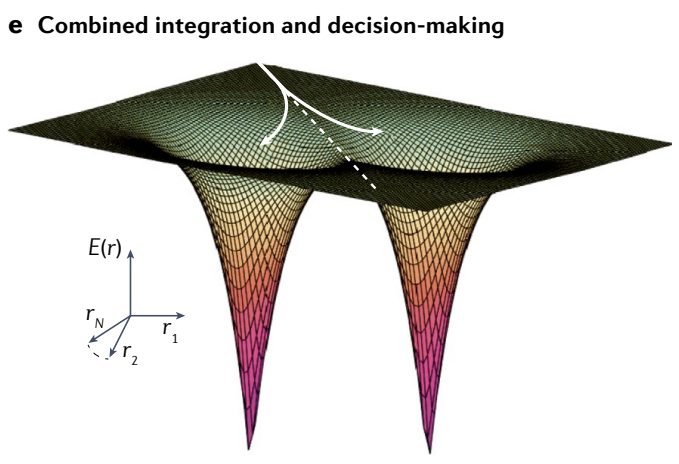

e, The energy ($E$) landscape of a combined integration and decision-making network: inputs push the state left or right, and as the system integrates, the network state also moves towards one of two discrete attractors (left and right; white arrows, two sample trajectories). Arrival in the basin of one of the discrete attractors is a decision point.

e、积分和决策网络的能量 ($E$) 景观: 输入向左或向右推动状态, 并且随着系统积分, 网络状态也移动到两个离散吸引子之一 (左和右; 白色箭头, 两个样本轨迹). 到达其中一个离散吸引子的盆地是一个决策点.

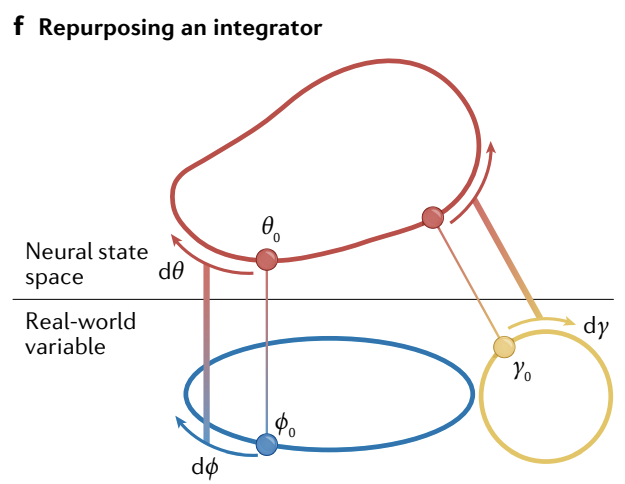

f, An integrator can be quickly re-purposed to represent multiple different and new external variables simply by yoking its velocity shift mechanism to different external velocities cues through feedforward learning.

This mechanism also supports zero-shot learning and inference: given an initial state and an input velocity trajectory, it will generate a self-consistent representation for the current state even if the trajectory is different and new each time.

f、积分器可以通过将其速度偏移机制与不同的外部速度线索通过前馈学习联系起来, 快速重新用于表示多个不同且新的外部变量.

这种机制还支持 零样本学习 和推理: 给定初始状态和输入速度轨迹, 即使每次轨迹不同且全新, 它也会生成当前状态的自洽表示.

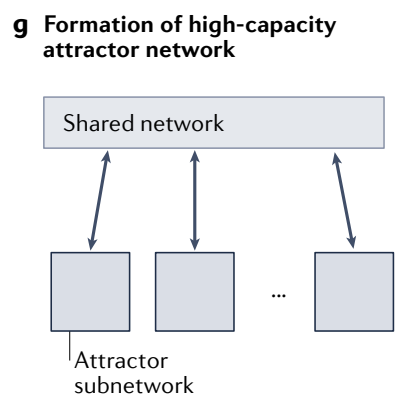

g, A set of (continuous or discrete) attractor subnetworks (red boxes at bottom) can interact bidirectionally with a shared network to form a high-capacity attractor network.

g、一组 (连续或离散) 吸引子子网络 (底部的红色框) 可以与共享网络双向交互以形成高容量吸引子网络.

h, Mixed modular representations can enable representation of inputs of different dimensions, by reusing the same attractors of fixed dimension each. Velocities ($v_{i}$) from external spaces of potentially different dimension are selected by a set of selection signals ($s_{i}$). The selected velocity (green) is routed through random projections to a set of $M$ modular integrator networks of dimension $K$ each. This kind of mixed modular circuit can interchangeably represent various input spaces of dimension $D \leq MK$ while smoothly trading off resolution for dimension.

h、混合模块化表象 可以通过重复使用每个固定维度的相同吸引子来表示不同维度的输入. 一组选择信号 ($s_{i}$) 选择来自潜在不同维度的外部空间的速度 ($v_{i}$). 选择的速度 (绿色) 通过随机投影路由到一组每个维度为 $K$ 的 $M$ 个模块化积分器网络. 这种混合模块化回路可以互换地表示各种维度为 $D \leq MK$ 的输入空间, 同时平滑地权衡分辨率与维度.

Another way to characterize the relationship between attractors and network structure is to consider the ‘inverse’ problem: given a set of attractors, what network structure could generate it?

Neuroscientists want to solve the inverse problem to make predictions about underlying mechanisms and, because neural activations are more readily observed than synaptic weights, the inverse problem is more frequently encountered than the forward problem.

By contrast, evolution, the brain and artificially intelligent systems must solve the inverse problem to be able to perform computations that require a given type of attractor dynamics (discussed below). Theoretical neuroscience has discovered some solutions to the inverse problem for different types of attractors, as we describe below.

另一种表征吸引子与网络结构之间关系的方法是考虑 “逆” 问题: 给定一组吸引子, 什么网络结构可以生成它?

神经科学家希望解决逆问题以对潜在机制进行预测, 并且由于神经激活比突触权重更容易观察到, 因此逆问题比正向问题更常见.

相比之下, 进化、大脑和人工智能系统必须解决逆问题, 以便能够执行需要特定类型吸引子动力学的计算 (下面讨论). 正如我们下面描述的那样, 理论神经科学已经发现了一些不同类型吸引子的逆问题的解决方案.

Discrete attractors

A well-known prescription for creating a set of discrete attractors at user-defined points is given by the Hopfield model5 (Fig. 1a).

Input patterns of neural activation are inscribed into the network weights through a Hebbian-like learning rule, such that co-active neurons are connected by excitatory interactions and inhibit all the rest. Thus, these patterns stabilize themselves and become attractor states. If a sufficiently small number of patterns are learned, they can be retrieved from partial or corrupted versions of the stored states, and thus the network can be said to store content-addressable memories.

More generally, the attractors of simple rate-based networks with arbitrary symmetric weight matrices and without communication delays consist entirely of fixed points.

Some non-symmetric networks can also support point attractors, but not generically, and they can require additional mechanisms such as homeostatic plasticity.

一种众所周知的在自定义的点创建一组离散吸引子的处理方法是 Hopfield 模型 (图 1a).

通过类似 Hebbian 的学习规则将神经激活的输入模式 铭刻 到网络权重中, 使得共同激活的神经元通过兴奋性相互作用连接并抑制其余部分. 因此, 这些模式稳定自身并成为吸引子状态. 如果学习的模式数量足够少, 则可以从存储状态的部分或损坏版本中检索它们, 因此可以说网络存储了 内容可寻址记忆.

更一般地说, 具有任意对称权重矩阵且没有通信延迟的简单基于速率的网络的吸引子完全由 不动点 组成.

一些非对称网络也可以支持点吸引子, 但不是通用的, 并且它们可能需要诸如稳态可塑性之类的附加机制.

Attractor states in Hopfield-like networks typically have highly overlapping neural memberships, even when they are well separated in the state space (Fig. 1a, middle column). Thus, there is not a clear notion of distinct ‘cell assemblies’. In a special case of Hopfield networks, neurons are partitioned into largely disjointed groups with self-excitation within groups and inhibition between groups.

In these winner-take-all (WTA) networks, the attractor states consist of largely non-overlapping active cell groups, which might then be called ‘assemblies’ (Fig. 1b).

Hopfield 类网络中的吸引子状态通常具有高度重叠的神经元成员, 即使它们在状态空间中分离良好 (图 1a, 中间列). 因此, 没有明确的 “细胞集群” 概念. 在 Hopfield 网络的一个特殊情况下, 神经元被划分为大致不相交的组, 组内具有自我兴奋, 组间具有抑制.

在这些 赢家通吃 (WTA) 网络中, 吸引子状态由大致不重叠的活跃细胞群组成, 然后可以称之为 “集群” (图 1b).

Continuous attractors

How can one construct networks with a continuum of stationary attractor states?

Weight matrices with a particular symmetry (across the diagonal) give rise to discrete attractors, as we have seen.

If the weights instead exhibit a continuous symmetry — for example, if the weight profiles are invariant across neurons (they look the same at each neuron, thus the symmetry is translational) — then the set of formed attractors will be related by the same symmetry and could thus form a continuous set.

如何构建具有连续静止吸引子状态的网络?

我们已经看到, 具有特定对角线对称性的权重矩阵会产生离散吸引子.

如果权重表现出连续对称性——例如, 如果权重配置在神经元之间是不变的 (它们在每个神经元处看起来相同, 因此对称性是平移的) ——那么形成的吸引子集将与相同的对称性相关联, 因此可以形成连续集.

The general principle for the formation of stationary continuous attractors is pattern formation. Simple and spatially local competitive interactions across the neural sheet lead to the emergence of spatially structured activity patterns that are stable states: neurons with excitatory coupling between them become co-active and suppress the rest of their neighbours through inhibition in what is known as a linear Turing instability.

形成静止连续吸引子的基本原理是 模式形成. 神经片上简单且空间局域的竞争性相互作用导致空间结构化活动模式的出现, 这些模式是稳定状态: 通过兴奋性耦合的神经元变得共同活跃, 并通过抑制抑制其余近邻, 这被称为线性 Turing 不稳定性.

Three conditions are generally sufficient (although not strictly necessary) to provide a solution to the inverse problem for forming stationary continuous attractors (Box 1).

First, the system must include nonlinear neurons with saturating responses or inhibition-dominated recurrent interactions and a uniform excitatory drive to keep network activity bounded.

Second, the system must involve sufficiently strong recurrent weights with competitive dynamics in the form of local excitation or disinhibition, with broader inhibition, to drive spontaneous pattern formation through the Turing instability; these patterns become the attractor states.

Last, the system requires some continuous symmetry in the weights (a continuous weight symmetry is one where as some variable is varied continuously, the weights remain invariant), such as translational or rotational invariance (Fig. 1c,d), to ensure a continuum of attractor states.

通常有三个条件足以 (尽管不是严格必要的) 为 “形成静止连续吸引子” 提供逆问题的解 (框 1).

-

首先, 系统必须包括具有饱和响应的非线性神经元, 或以抑制为主导的递归相互作用以及均匀的兴奋驱动以保持网络活动有界.

-

其次, 系统必须涉及足够强的 递归权重, 具有局部兴奋或去抑制形式的竞争动力学, 以及更广泛的抑制, 以通过 Turing 不稳定性驱动自发模式形成; 这些模式成为吸引子状态.

-

最后, 系统需要权重中的某种连续对称性 (连续权重对称性是指随着某个变量的连续变化, 权重保持不变) , 例如平移或旋转不变性 (图 1c、d) , 以确保吸引子状态的连续性.

BOX 1

Attractor dynamics, anatomical topography and weight symmetries

Anatomical topography, in which functionally similar neurons are near one another, is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for the existence of an attractor, because any low-dimensional attractor network is mathematically unchanged if all weights are preserved but neuron locations are scrambled. However, if the network is merely a spatially scrambled version of the idealized model, then the symmetries of the weight matrix can be revealed after an appropriate reordering of the neurons. An advantage of anatomical topography from a biological perspective is that it can reduce the complexity of development, in that wiring decisions can be guided by spatial proximity rather than depending entirely on activity or other target cell-signalling mechanisms. For example, the locally competitive interactions of grid and head-direction circuit models could be largely constructed through local arborization. Anatomical topography also reduces overall wiring length in the mature circuit. However, a circuit with three-dimensional dynamics or higher that are represented in an unfactorizable form cannot be embedded topographically in a two-dimensional cell layout, limiting the feasibility of topographic layouts for circuits that represent higher-dimensional unfactorizable manifolds.

功能相似的神经元彼此靠近的解剖拓扑既不是吸引子存在的必要条件, 也不是充分条件, 因为如果保留所有权重但神经元位置被打乱, 任何低维吸引子网络在数学上都是不变的. 然而, 如果网络仅仅是理想化模型的空间混乱版本, 那么在适当重新排序神经元后, 可以揭示权重矩阵的对称性. 从生物学角度来看, 解剖拓扑的一个优势是它可以减少发展的复杂性, 因为布线决策可以通过空间接近性来指导, 而不完全依赖于活动或其他目标细胞信号机制. 例如, 网格和头部方向回路模型的局部竞争性相互作用可以主要通过局部树突形成来构建. 成熟回路中的解剖拓扑还减少了整体布线长度. 然而, 具有三维动力学或更高维度动力学且以不可分解形式表示的回路无法在二维细胞布局中进行拓扑嵌入, 这限制了表示高维不可分解流形的回路的拓扑布局的可行性.

In addition, the posited weight symmetries in simple models of attractors need not exist in a biological instance of the circuit with the same dynamics: unscrambling or reordering neurons may not be sufficient to reveal the symmetries. Consider, for example, a scenario in which low-dimensional attractor dynamics are generated by a recurrent network of $N$ neurons, but are only needed downstream in a set of $M < N$ neurons. In this situation, the weight symmetries needed for continuous-attractor dynamics can be spread across both the recurrent and readout networks, such that the weights of the recurrent network alone will not reflect the relevant symmetries. Unveiling the symmetry in the circuit weights will require combining the readout weights with the recurrent ones.

此外, 简单吸引子模型中假定的权重对称性不一定存在于具有相同动力学的回路的生物实例中: 打乱或重新排序神经元可能不足以揭示对称性. 例如, 考虑这样一种情况: 低维吸引子动力学由 $N$ 个神经元的递归网络生成, 但仅在下游的一组 $M < N$ 个神经元中需要. 在这种情况下, 连续吸引子动力学所需的权重对称性可以分布在递归和读出网络中, 因此仅递归网络的权重将不会反映相关的对称性. 揭示回路权重中的对称性将需要将读出权重与递归权重结合起来.

These considerations give rise to a hypothesis for circuits with continuous attractors of dimension $\leq 2$: evolutionarily conserved circuits that do not require extensive early experience should be topographically organized. We might thus predict that the circuit that originates head-direction signals in mammals should be topographically organized. By contrast, if low-dimensional dynamics only emerge on the basis of activity-dependent plasticity with repetitive training, we may not expect the circuit to be topographically organized (or even localized to a single brain region).

这些考虑为维度 $\leq 2$ 的连续吸引子回路提出了一个假设: 不需要广泛早期经验的进化保守回路应该是拓扑组织的. 因此, 我们可以预测起源于哺乳动物头部方向信号的回路应该是拓扑组织的. 相比之下, 如果低维动力学仅基于具有重复训练的活动依赖性可塑性出现, 我们可能不期望该回路是拓扑组织的 (甚至不局限于单个大脑区域).

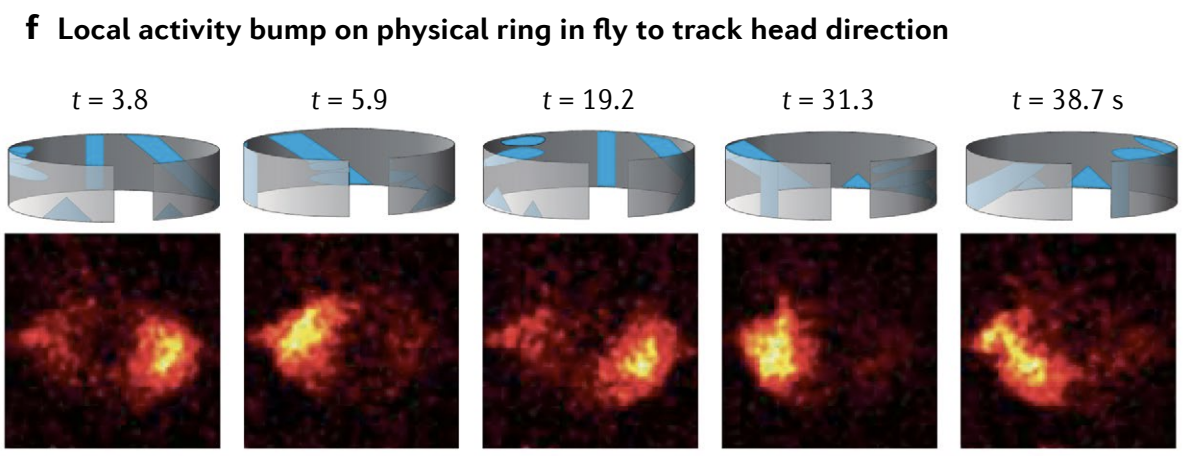

Remarkably, despite these caveats, and in a beautiful example of the predictive power of simple theories in neuroscience, empirical evidence from the anatomy of the zebrafish oculomotor integrator and the fly head-direction circuit in the past few years shows that nature has used precisely the hypothesized constructions proposed in simple circuit models to build some integrator networks.

值得注意的是, 尽管存在这些警告, 并且在神经科学中简单理论预测能力的一个美丽例子中, 过去几年来自斑马鱼眼动积分器和果蝇头部方向回路解剖学的实证证据表明, 自然界已经使用了简单回路模型中提出的假设构造来构建一些积分器网络.

A special set of networks generate continuous-attractor dynamics without pattern formation: those with linear, planar or hyperplanar attractors that are generated by neurons with linear or near-linear response functions.

In circuits of linear neurons, the feedback within the network is a linear function of activity ($Wr$, where $W$ is the weight matrix and $r$ are the neural activities), as is the activity decay (given by $−r$). Such networks can stabilize non-zero activity states simply by tuning positive feedback to cancel the decay. The matrix $W$ can direct feedback in state space; if feedback is directed largely along one dimension, the network can support a line attractor (Fig. 1e). If it is directed equally along two or more dimensions, it can support a plane or hyperplane attractor. To create long-lived attractors requires that the network feedback magnitude is finely tuned to precisely cancel the decay, in contrast to pattern-forming continuous-attractor systems where the weight shapes (but not magnitudes) are tuned to maintain continuous symmetry across neurons.

一组特殊的网络在没有模式形成的情况下产生连续吸引子动力学: 那些由具有线性或近线性响应函数的神经元生成的线性、平面或超平面吸引子.

在线性神经元回路中, 网络内的反馈是活动的线性函数 ($Wr$, 其中 $W$ 是权重矩阵, $r$ 是神经活动) , 活动衰减也是如此 (由 $−r$ 给出). 通过调节正反馈以抵消衰减, 这样的网络可以稳定非零活动状态. 矩阵 $W$ 可以在状态空间中引导反馈; 如果反馈主要沿一个维度引导, 网络可以支持线性吸引子 (图 1e). 如果它在两个或更多维度上均匀引导, 它可以支持平面或超平面吸引子. 要创建长寿命吸引子, 要求网络反馈幅度被精细调制以精确抵消衰减, 这与模式形成的连续吸引子系统形成对比, 在这些系统中, 权重形状 (而不是幅度) 被调制以保持神经元之间的连续对称性.

系统的线性动力学:

$$ \frac{\mathrm{d}r}{\mathrm{d}t} = Wr - r $$

$W$ 的为 1 的特征值数量确定了吸引子的维数. 比如线吸引子(1 个), 平面吸引子(2 个)…

$>1$ 代表激活发散, $<1$ 代表激活衰减.

Non-stationary continuous attractors

Large non-symmetric networks with nonlinear neurons and strong connectivity generically exhibit limit-cycle attractors or chaotic dynamics.

Just as point attractors emerge generically in large networks with strong symmetric weights and bounded state spaces, chaotic attractors emerge generically in large recurrent networks with strong asymmetric weights.

Adequate asymmetries are easily achieved if excitatory and inhibitory synapses emerge from distinct sets of neurons, as biologically necessitated by Dale’s law.

含有非线性神经元和强连接性的非对称大型网络通常表现出 极限环吸引子 或 混沌动力学.

正如在具有强对称权重和有界状态空间的大型网络中点吸引子普遍出现一样, 在具有强非对称权重的大型递归网络中 混沌吸引子 也普遍出现.

如果兴奋性和抑制性突触来自不同的神经元组 (正如 Dale 定律在生物学上所必需的那样) , 则可以轻松实现足够的非对称性.

Despite the complexity of chaotic dynamics, chaotic attractors are also highly structured in that they typically exist in a relatively low number of dimensions compared with the number of neurons in the network.

Non-symmetric networks that are dominated by inhibition exhibit a single attractor at zero activity, although the flow towards the attractor in response to perturbations can involve large transients in neural activation that temporarily move the state further away from the attractor.

尽管混沌动力学复杂, 但混沌吸引子也具有高度结构化的特征, 因为它们通常存在于相比 网络中神经元的数量 低得多的维数中.

以抑制为主导的非对称网络在零激活下展现出单一吸引子, 尽管响应扰动时, 朝向吸引子的流动可能涉及神经激活中的大瞬态, 这些瞬态会暂时使状态远离吸引子.

Attractors for neural computation

A system could theoretically be perfectly tuned such that every point in state space is a neutrally stable attractor, and thus the system has maximally high-dimensional attractor dynamics.

However, because the robustness of attractor networks is related to the low-dimensionality of the attractor states (as discussed below), the system would lose most of its interesting computational properties: error correction or noise tolerance, nearest-neighbour computation, pattern completion and content-addressable memory. It could perform integration, but with no robustness to noise.

As such, networks with low-dimensional attractor dynamics exhibit myriad properties that can be vital for computation in the brain These include robust representation, memory, sequence generation, integration, and robust classification and decision-making ideas that have been extensively explored in the literature.

In a later section, we describe how, although attractor dynamics may be rigid and invariant as needed for the roles listed above, recent theoretical and experimental findings are beginning to reveal how these rigid constructions may also be exploited to perform flexible computation through reuse and recombination across tasks.

一个系统理论上可以被完美 调制, 使得状态空间中的每个点都是一个中性稳定的吸引子, 因此系统具有最大维度的吸引子动力学.

然而, 由于吸引子网络的稳健性与吸引子状态的低维性有关 (如下所述) , 系统将失去其大部分有趣的计算属性: 错误纠正或噪声容忍、最近邻计算、模式完成和内容可寻址记忆. 它可以执行积分, 但对噪声没有鲁棒性.

因此, 具有低维吸引子动力学的网络表现出无数对于大脑计算至关重要的属性. 这些包括稳健的表示、记忆、序列生成、积分, 以及在文献中已被广泛探索的稳健分类和决策思想.

在后面的章节中, 我们描述了尽管吸引子动力学可能是刚性的且不变的, 以满足上述需要, 但最近的理论和实验发现开始揭示如何利用这些 刚性结构 通过跨任务的复用和重组来执行灵活计算.

Representation and memory

A representation of a set of inputs means the assignment of inputs to representational states (not necessarily on a one-to-one basis), with the ability to reproducibly retrieve those states (‘labels’) when cued.

Attractor networks provide a stable internal set of states that can be used for reproducible representation of discrete or analogue variables, by mapping states in the world to the attractor states. One way to achieve this mapping is through a feedforward learning process that associates each external state with an internal attractor state (Fig. 2a).

对一组输入的表示意味着将输入分配给表示状态 (不一定是一对一的基础) , 并且在提示时能够可重复地检索这些状态 ( “标签” ).

吸引子网络提供了一组稳定的内部状态, 可用于通过将世界中的状态映射到吸引子状态来可重复地表示离散或模拟变量. 实现这种映射的一种方法是通过 前馈学习过程, 将每个外部状态与内部吸引子状态相关联 (图 2a).

An attractor network can exhibit two kinds of memory.

The first is in the structure of the weights, which specify the set of all attractors. If these weights are specified through an input-driven learning process, this is a form of long-term memory about the inputs.

The second kind of memory is the ability to maintain persistent activity in a stationary attractor state: if a system with multiple stationary attractor states is initialized in one of them, it will tend to remain at or near the same state for some time. In other words, the activation levels of the neurons contributing to that state persist while the system remains in the state. This persistent activity response is thus a form of short-term memory of the input that initialized the circuit. If these persistent memory states can be activated without an explicit address, using just the content (or partial content) of the memory, they are content-addressable.

吸引子网络可以表现出两种记忆.

第一种是存储于权重的结构, 它确定了所有吸引子状态的集合. 如果这些权重是通过输入驱动的学习过程确定的, 这是一种关于输入的长期记忆形式.

第二种记忆来自网络在一静止吸引子状态中维持持续活动的能力: 如果一系统具有若干静止吸引子状态, 并且设置初态为其中一个吸引子状态, 它将倾向于在一段时间内保持在该状态或附近. 换句话说, 贡献于该状态的神经元的激活水平在系统保持在该状态时持续存在. 因此, 这种持续的活动响应是一种对初始化回路的输入的短期记忆形式. 如果这些持续的记忆状态可以在没有 显式地址 的情况下被激活, 仅使用记忆的内容 (或部分内容) , 则它们是内容可寻址的.

The short-term memory function of attractors depends on the prior formation of stable states through long-term plasticity.

For instance, in Hopfield-like networks, states cannot persist if they were not first trained to be attractor states. Even models of short-term memory that are based on presynaptic facilitation, rather than persistent activity, rely implicitly on prior long-term associative plasticity to construct recurrently stabilized neural ensembles that can be reinstated by random inputs. (Additionally, these models are not activity-silent in the delay period, in the sense that they would require ongoing activity to refresh the facilitation state over longer delays and to generate robustness against random background activity that would facilitate different synapses.)

In other words, these presynaptic facilitation models cannot explain short-term memory for entirely novel inputs; however, combinations of attractors could enable more flexible short-term memory, as we discuss later.

吸引子的短期记忆功能依赖于通过长期可塑性形成稳定状态的先验.

例如, 在 Hopfield 类网络中, 如果状态没有首先被训练为吸引子状态, 则它们无法持续存在. 即使是基于 突触前易化 而不是持续活动的短期记忆模型, 也隐式地依赖于先前的长期联想可塑性来构建可以通过随机输入重新建立的递归稳定神经元集合. (此外, 这些模型在延迟期间并非活动静默, 因为它们需要持续的活动来刷新促进状态以应对更长的延迟, 并生成对随机背景活动的鲁棒性, 这些活动会促进不同的突触. )

换句话说, 这些突触前促进模型无法解释对完全新颖输入的短期记忆; 然而, 正如我们稍后讨论的那样, 吸引子的组合可以实现更灵活的短期记忆.

De-noising representations and memories

If representational states are attractors, then the representations are robust in the sense that they perform de-noising: if the input cues or initial conditions reflect noisy or corrupted versions of an attractor state, the dynamics drive the state to a point on the representational attractor (Fig. 2b, inset).

When attractors form a continuous manifold of dimension $K\ll N$, where $N$ is the number of neurons in the circuit, all noise in $N-K$ dimensions is erased. A noise ball of unit radius in $N$ dimensions (corresponding to random independent noise per neuron) has a projection of size only $\sim\sqrt{K/N}\ll 1$ along $K$ dimensions.

If $K$ is low-dimensional, as is often the case, and $N$ ranges from $10^2$ to $10^7$ as estimated before for common microcircuits, this constitutes a massive reduction in the sensitivity of the state to internal or input noise (Fig. 2b). Thus, most noise is rendered impotent by attractor dynamics.

如果表象状态是吸引子, 那么表象在某种意义上是稳健的, 因为它们执行去噪: 如果输入提示或初始条件反映了加噪或损坏的吸引子状态, 动力学会将状态驱动到表象的吸引子 (图 2b, 插图).

当吸引子形成维度为 $K\ll N$ 的连续流形时, 其中 $N$ 是回路中神经元的数量, $N-K$ 维中的所有噪声都被抹去. 在 $N$ 维中的单位半径噪声球 (对应于每个神经元的随机独立噪声) 在 $K$ 维上的投影大小仅为 $\sim\sqrt{K/N}\ll 1$.

如果 $K$ 是低维数, 正如通常情况一样, 并且 $N$ 范围从之前估计的常见微回路的 $10^{2}$ 到 $10^{7}$, 这构成了对状态对内部或输入噪声敏感性的巨大降低 (图 2b). 因此, 大多数噪声通过吸引子动力学变得无效.

De-noising owing to attractor dynamics is especially important for memory maintenance as, otherwise, noise-induced deviations would accumulate and grow over time.

Discrete attractors continually erase all noise by mapping perturbed states back to the point attractor, resulting in zero drift. With continuous attractors as memory states, all noise orthogonal to the manifold is corrected; thus, there is a net reduction of the effects of noise by the factor $\sim\sqrt{K/N}\ll 1$ (refs.45,55).

However, all states on the attractor manifold are neutrally stable, so the state can drift along the attractor. As such, components of noise along the $K$ attractor dimensions are not internally corrected and cause an accumulating drift away from the initial state, with variance proportional to $KT/N$, where $T$ is the elapsed time. Thus, through the $1/N$ decrease in variance, even continuous memory states can be well stabilized in sufficiently large attractor networks.

吸引子动力学引起的去噪对于记忆维持尤为重要, 否则, 噪声引起的偏差会随着时间的推移而积累和增长.

离散吸引子通过将扰动状态映射回点吸引子来不断抹去所有噪声, 产生零漂移. 对于作为记忆状态的连续吸引子, 所有正交于流形的噪声都被纠正; 因此, 噪声效应净减少了 $\sim\sqrt{K/N}\ll 1$ 的因子 (参考文献 45、55).

然而, 吸引子流形上的所有状态都是中性稳定的, 因此状态可以沿着吸引子漂移. 因此, 沿着 $K$ 吸引子维度的噪声分量不会被内部纠正, 并导致远离初始状态的累积漂移, 其方差与 $KT/N$ 成正比, 其中 $T$ 是经过的时间. 因此, 通过 $1/N$ 方差的降低, 即使是连续的记忆状态也可以在足够大的吸引子网络中得到很好的稳定.

Although content-addressable long-term memory and error reduction can be instantiated through feedforward computations involving only a few steps in place of attractor dynamics, recurrent attractor dynamics are indispensable for the generation of persistent activity states (and thus for short-term memory through persistent activity) and integration, as we discuss below.

尽管内容可寻址的长期记忆和错误减少可以通过涉及仅几个步骤的前馈计算来实现, 而不是吸引子动力学, 但正如我们下面讨论的那样, 递归吸引子动力学对于生成持续活动状态 (因此通过持续活动进行短期记忆) 和积分是不可或缺的.

Robust classification

When there are finitely many separated attractors (each a discrete attractor or a continuous manifold), states that are not initially on one of the attractors will flow to one of the attractors. An input to the network can then be classified according to the attractor to which the network state flows after initialization by the input. We can now identify inputs based on the attractors they flow to, a mechanism of classification. If the dynamics of the network further correctly assign corrupted versions of an input to the same attractor state as the uncorrupted input, this constitutes robust classification.

In other words, the dynamical basins of attraction of the network must align with the Voronoi regions of the attractor states (that is, corrupted inputs that are closest in distance to one of the uncorrupted inputs should flow to that input’s attractor through the dynamics and not another). This is approximately the case for attractor networks operating well below capacity, but typically deteriorates when attractor networks are pushed towards their capacity.

当存在有限数量的分离吸引子 (每个都是离散吸引子或连续流形) 时, 最初不在其中一个吸引子上的状态将流向其中一个吸引子. 然后, 可以根据网络状态在输入初始化后流向的吸引子对网络的输入进行分类. 我们现在可以根据它们流向的吸引子来识别输入, 这是一种分类机制. 如果网络的动力学进一步将输入的损坏版本正确地分配给与未损坏输入相同的吸引子状态, 这就构成了稳健分类.

换句话说, 网络的动力谷地必须与吸引子状态的 Voronoi 区域对齐 (即, 与未损坏输入距离最近的损坏输入应该通过动力学流向该输入的吸引子, 而不是另一个). 对于在容量以下良好运行的吸引子网络来说, 这大致是正确的, 但当吸引子网络被推向其容量时通常会恶化.

Integration

Single neurons integrate their inputs, but usually can only do this over the timescales associated with their membrane capacitances, typically 10-100 ms. Continuous-attractor dynamics can enable neural circuits to integrate over much longer timescales (in the order of about 1-100 s).

单个神经元积分它们的输入, 但通常只能在与其膜电容相关的时间尺度上进行积分, 通常为 10-100 毫秒. 连续吸引子动力学可以使神经回路在更长的时间尺度上进行积分 (大约 1-100 秒).

A pattern-forming continuous-attractor network requires an additional mechanism to gain the functionality of an integrator: a way to shift the internal state along the attractor in response to an input that encodes changes in the external variable (Fig. 2d, left).

Conceptually, the simplest way to build a shift mechanism is by a copy-and-offset construction: construct multiple copies or subpopulations of the attractor network, each with slightly offset (asymmetric) weights in the sense that active neurons centre their excitation or point of maximal disinhibition slightly offset from themselves on the neural sheet (for example, see that the network in Fig. 1g is a slightly asymmetric version of the network in Fig. 1c). The states in each such network will then form a limit-cycle attractor, with patterns of activity flowing in the direction of the asymmetry in each copy.

If opposing copies are coupled together, the pattern is stabilized through a push-pull balance. A velocity input whose components project differentially to the copies will break the push-pull balance, driving the pattern along the flow direction of the more active copy (Fig. 1g).

Thus, the total direction and magnitude of the shift of the pattern, corresponding to movement along the attractor manifold, represents the time integral of the velocity input to the network. This common principle unifies the mechanisms across diverse integrator models.

形成模式的连续吸引子网络需要一个额外的机制来使获得积分器的功能: 一种编码 外部变量 变化量的输入, 沿吸引子平移内部状态的方法 (图 2d, 左).

从概念上讲, 构建平移机制的最简单方法是通过 复制和偏移结构: 构建多个吸引子网络的备份或子群体, 每个备份具有略微偏移 (非对称) 权重, 这意味着活跃神经元将其兴奋或最大去抑制点稍微偏离神经片上的自身中心 (例如, 参见图 1g 中的网络是图 1c 中网络的略微非对称版本). 然后, 每个这样的网络中的状态将形成 极限环吸引子, 激活模式沿着每个副本中非对称性的方向流动.

如果将相反的副本耦合在一起, 通过推-拉平衡稳定模式. 其分量差异性投影到副本的速度输入将打破推拉平衡, 沿着更活跃副本的流动方向驱动模式 (图 1g).

因此, 模式的总方向和幅度偏移, 对应于沿吸引子流形的运动, 表示网络对速度输入的时间积分. 这一共同原理统一了各种积分器模型中的机制.

数学上

$$ x(t) = x(t_{0}) + \int_{t_{0}}^{t}\dot{x}(\tau)\mathrm{d}\tau $$

$x$: bump 位置; $\dot{x}$: bump 移动速度.

Decision-making

If, instead of a velocity signal, the input to an integrator network consisted of temporally varying positive and negative evidence in support of each of two options (Fig. 2d, right) (or in the case of multiple options, evidence vectors instead of velocity vectors), the network would integrate those inputs and thus perform evidence accumulation.

如果, 积分器网络的输入不是速度信号, 而是支持两个选项中每个选项的时间变化的正负证据 (图 2d, 右) (或者在多选情况下, 是证据向量而不是速度向量) , 则网络将积分这些输入, 从而执行 证据积累.

设证据输入为 $e(t) = e_{A}(t) - e_{B}(t)$, 则证据积累为

$$ s(t) = s(0) + \int_{0}^{t}e(\tau)\mathrm{d}\tau,\quad \text{or }\mathbf{s}(t) = \mathbf{s}(0) + \int_{0}^{t}\mathbf{e}(\tau)\mathrm{d}\tau $$

Decision-making can be viewed as a selection process applied to an integrator that is based on a readout that detects when the integrator state has accumulated enough evidence and moved past a decision threshold.

The selection process can be external to the integrator, in the form of a readout circuit that detects such threshold crossings and outputs the decision.

Alternatively, the selection process can be built into the dynamics of the integrator itself, in the form of a more complex attractor landscape, in which the states move along a continuous attractor but, at some point, the continuous attractor gives way to a pair of discrete attractors, towards which the states flow (Fig. 2e).

Neural WTA models implement such a hybrid analogue-discrete computation. The parameters of WTA networks determine the balance between integration dynamics and competitive dynamics, and thus how well the network integrates later evidence: when the network is tuned to be a perfect integrator, its response to inputs is gradual, and small amounts of evidence cause (reversible) flow along the continuous-attractor manifold. In cases in which competition dominates, the response to evidence is a fast flow towards one of the discrete attractors; beyond a point, the flow is nearly irreversible, leading to rapid decision-making and the discounting of later evidence.

可以将决策视为应用于积分器的选择过程, 基于检测积分器状态何时积累足够证据并超过决策阈值的读出.

选择过程可以是积分器外部的, 以读出回路的形式检测此类阈值交叉并输出决策.

或者, 选择过程可以内置于积分器本身的动力学中, 以更复杂的吸引子景观的形式, 其中状态沿着连续吸引子移动, 但在某些点上, 连续吸引子让位于一对离散吸引子, 状态朝向这些吸引子流动 (图 2e).

神经 WTA 模型实现了这种 混合模拟-离散计算. WTA 网络的参数决定了积分动力学和竞争动力学之间的平衡, 从而决定了网络整合后续证据的能力: 当网络被调制为完美积分器时, 其对输入的响应是渐进的, 少量证据会导致沿连续吸引子流形的 (可逆) 流动. 在竞争占主导地位的情况下, 对证据的响应是快速流向其中一个离散吸引子; 超过某一点后, 流动几乎是不可逆的, 导致快速决策和对后续证据的折扣.

Neural WTA networks can leverage specific neural non-linearities to accurately and rapidly (in $\sim \log{(N)}$ time) make the best decision among $N$ alternatives, even if the presented data are noisy (fluctuating over time around their means) and even if the number of options varies over orders of magnitude.

神经 WTA 网络可以利用特定的神经非线性, 以准确且快速 (在 $\sim \log{(N)}$ 时间内) 在 $N$ 个备选方案中做出最佳决策, 即使所呈现的数据是嘈杂的 (围绕其均值随时间波动) , 即使选项数量变化了几个数量级.

Sequence generation

Attractor dynamics can be important for stabilizing another longtimescale behaviour: the generation of sequences. Robust sequences can be constructed as low-dimensional limit-cycle attractors, in which high-dimensional perturbations are corrected while along the attractor, there is a systematic, periodic or quasiperiodic flow of states.

The attractor property that affords ongoing de-noising is important for preventing spatial dispersion and temporal dissipation of the activity packet during sequence generation.

吸引子动力学对于稳定另一种长期行为也很重要: 序列生成. 稳健的序列可以构建为低维极限环吸引子, 在这种吸引子中, 高维扰动被纠正; 沿着吸引子(流形), 状态存在系统的且(准)周期性的流动.

保持去噪的吸引子属性对于防止序列生成过程中活动包的 空间频散 和 时间耗散 非常重要.

Similar to the case for stationary attractor manifolds, the small components of noise along the limit-cycle attractors are not correctable and lead to a gradual accumulation of drift, which for sequence generation is manifest as timing variability: the standard deviation in the time of reaching the $T$th state in the sequence is predicted to grow as $\sqrt{T}$ for unbiased random drift along the attractor.

与静止吸引子流形的情况类似, 噪声沿极限环吸引子的小分量是不可纠正的, 并导致逐渐积累的漂移, 对于序列生成来说, 这表现为 时间变化性: 预计达到序列中第 $T$ 个状态的时间的 标准偏差 将随着沿吸引子的无偏置随机漂移而增长为 $\sqrt{T}$.

Evidence of attractors in the brain

Criteria for attractor dynamics

The fundamental predictions of attractor models centre on the statespace dynamics of the circuit, as initially explicitly discussed and tested in refs.9,15,77,78.

First, a system’s states should be found localized at or around a low-dimensional set of states that correspond to the attractors in the state space.

Second, a system’s state should flow quickly back to the low-dimensional state after perturbation.

Third, the set of attractor states — quantified either by direct characterization of the full state space or by the relationships between cells — should be invariant, persisting over time and after removal of tuned input, across conditions, across behavioural states and even when there are induced variations in the mapping from internal states to external inputs.

Fourth, integrator networks should further exhibit the property of isometry, whereby lengths of coding space along a dimension are allocated to equal displacements along a dimension of the external variable.

Additional predictions of attractor dynamics models, that are not as fundamental in the sense that they are not theoretically necessary or sufficient but are nevertheless of high importance because they are highly supportive of the mechanisms of attractor dynamics, are anatomical and structural correlates: the existence of low-dimensional physical structures and directly visible symmetries in connectivity between cells.

吸引子模型的基本预测集中在回路的状态空间动力学上, 最初在参考文献 9、15、77、78 中明确讨论和测试.

首先, 系统的状态应定位在与状态空间中的吸引子对应的低维状态集上或附近.

其次, 系统的状态在扰动后应迅速流回低维状态.

第三, 吸引子状态集——通过 对完整状态空间的直接表征 或通过 细胞之间的关系 进行量化——应是不变的, 在时间上持续存在, 并且在去除调制输入后, 在不同条件下、不同行为状态下, 甚至在内部状态到外部输入的映射发生诱导变化时也是如此.

第四, 积分器网络还应表现出 等距性 的特性, 即编码空间沿某一维度的长度分配给外部变量某一维度上的相等位移.

比如, 网络状态沿环移动 10 度对应真实头朝向移动 10 度. 网络活动空间与物理空间存在等比例映射.

此外,吸引子动力学模型还有一些附加预测——这些预测在理论上并非必要或充分,但仍然非常重要,因为它们为吸引子动力机制提供了强有力的支持——即解剖和结构方面的对应特征:包括低维物理结构的存在,以及细胞之间连接中可直接观察到的对称性。

As we have seen, attractor networks dynamics need not be used by the brain in an autonomous setting: inputs that drive attractor networks can be an important part of their function, for instance in integration and evidence accumulation.

Nevertheless, because attractor systems are characterized by their internally generated or autonomous dynamics, putative attractor networks are best tested in conditions that minimize external cues that are time-varying or tuned to provide localized inputs along the putative attractor — that is, in an effectively autonomous setting.

正如我们已经看到的,吸引子网络的动力学并不必须在 完全自主 的情况下被大脑使用:驱动吸引子网络的外部输入也是其功能的重要组成部分,例如在积分和 证据累积 中。

大脑使用吸引子时, 有时令其自主维持, 有时令其接收外部输入从而积分.

然而,由于吸引子系统的一个定义特征是它们由内部产生的、即 自主动力学,因此,在测试候选的吸引子网络时,最好是在这样的条件: 使用那些能够最小化含时的外部提示,或者最小化那些调制为沿着所考察的吸引子维度提供局部化输入的提示——也就是,在一个“有效自主”的环境下进行测试。

Innovations in recording methods that have made it possible to record multiple neurons simultaneously in animals performing naturalistic behaviours have enabled crucial tests of these state-space predictions of attractor models described above. The newest methods provide activity data from thousands of neurons in a circuit, enabling characterization of the low-dimensional state-space dynamics of whole circuits.

记录方法的创新使得在动物进行自然行为时能够同时记录多个神经元活动,这为验证上述吸引子模型对状态空间的预测提供了关键测试手段。最新技术可获取神经回路中数千个神经元的活动数据,从而能够表征整个神经回路的低维状态空间动力学特性。

When the attractor manifolds have three or fewer dimensions, one can directly visualize them by projecting or embedding the highdimensional state spaces into dimension $\leq 3$. This can be done using methods such as principle components analysis, multidimensional scaling, tensor factorization or other linear methods for projection; or Isomap, locally linear embedding, $t$-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding, variational autoencoders, latent factor analysis via dynamical systems and nonlinear tensor factorization, among others, for nonlinear embedding.

These methods can also be useful when manifolds have dimension $\geq 3$ but are topologically simple. For topologically non-trivial structures (such as rings and tori), especially those of dimension $\geq 3$, topological data analysis methods become important.

当吸引子流形的维度为 3 或更少时, 可以通过将高维状态空间投影或 嵌入 到维度 $\leq 3$ 来直接可视化它们. 这可以使用主成分分析、多维尺度分析、张量分解或其他线性投影方法来完成; 或者使用 Isomap、局部线性嵌入、$t$ 分布随机邻域嵌入、变分自编码器、通过动力系统的潜在因子分析和非线性张量分解等进行非线性嵌入.

这些方法在流形的维度 $\geq 3$ 但拓扑结构简单时也很有用. 对于拓扑非平凡结构 (如环和环面) , 尤其是那些维度 $\geq 3$ 的结构, 拓扑数据分析方法变得重要.

Testing the first, second and third predictions of attractor models described above requires examination of the state-space structure of the population, rather than the more conventional characterization of relationships (tuning curves) between cell activity and input or output variables.

The most direct way to examine state-space structure is to record enough cells simultaneously that it is possible to characterize the full state-space manifold. However, the existence, stability and invariance of low-dimensional state-space structures (the first three predictions) can be inferred indirectly from smaller samples of simultaneously recorded cells, for example by characterizing invariant structure in pairwise cell-cell relationships, as has been successfully done in several studies.

测试上述吸引子模型的第一个、第二个和第三个预测需要检查集群的状态空间结构, 而不是更传统的表征细胞活动与输入或输出变量之间关系 (调制曲线).

检查状态空间结构的最直接方法是同时记录足够多的细胞, 以便能够表征完整的状态空间流形. 然而, 低维状态空间结构的存在、稳定性和不变性 (前三个预测) 可以从同步记录的较小样本中间接推断出来, 例如通过表征成对细胞-细胞关系中的不变结构, 正如几项研究中成功完成的那样.

The existence and stability of low-dimensional state-space structures are necessary but not sufficient for identification of recurrent attractor dynamics in a target network.

First, if the behaviours, circuit fluctuations and inputs to the network are themselves low-dimensional, then any observed low-dimensionality of the circuit states may be ascribed to those inputs and reveals little about intrinsic constraints imposed by the circuit.

Second, even if inputs and behaviours are highdimensional, a low-dimensional feedforward projection into the target network would generate low-dimensional states, and high-dimensional perturbations to the circuit would not persist.

The essential, defining prediction of attractor dynamics is that of invariance: because the states are internally generated and stabilized by strong recurrent connectivity, the population states and cell-cell relationships should be invariant when probed across time and across various input conditions, including when tuned input is removed and across waking and sleep. In simple terms, the stable low-dimensional states should be invariant across a broad range of conditions.

低维状态空间结构的存在和稳定性是识别目标网络中递归吸引子动力学的必要但不充分条件.

首先, 如果网络的行为、回路波动和输入本身是低维的, 那么回路状态的任何观察到的低维性都可以归因于这些输入, 并且几乎没有揭示回路施加的内在约束.

其次, 即使输入和行为是高维的, 进入目标网络的低维前馈投影也会生成低维状态, 并且对回路的高维扰动不会持续存在.

吸引子动力学的基本定义预测是不变性: 由于状态是由强递归连接内部生成和稳定的, 因此当跨时间和各种输入条件进行探测时, 群体状态和细胞-细胞关系应保持不变, 包括在去除调制输入以及在清醒和睡眠期间. 简单来说, 稳定的低维状态应在广泛条件下保持不变.

Next is the question of circuit localization: does a circuit exhibiting the key signatures of attractor dynamics give rise to these dynamics, or are they a readout of some other region?

Localization need not be a primary goal of establishing attractor dynamics: an important problem is to simply characterize whether the brain solves certain problems through attractor dynamics, regardless of which local circuits create these dynamics.

Nevertheless, the persistence of activity states in attractors can lend a helping hand to localization efforts. If a region gives rise to or is upstream (but not downstream) of the attractor dynamics, perturbations that alter its state along the set of attractors should persist after the perturbing drive is removed.

下一个问题是 回路定位: 表现出吸引子动力学关键特征的回路, 是(自行)产生了这些动力学, 还是它们是在读取某个其他脑区(的吸引子状态)?

这对于理解大脑功能的分工非常重要.

定位不必是建立吸引子动力学的首要目标: 一个重要的问题仅仅是弄清大脑是否通过吸引子动力学来解决某些问题,而不管究竟是哪一个局部神经回路生成了这些动力学.

然而,吸引子中活动状态的持续性可以帮助进行回路定位。如果一个脑区本身生成 (或处于吸引子动力学的上游,而不是下游) ,那么对其施加能够改变其在吸引子集合上位置的扰动后,在扰动输入移除之后,这些状态变化仍应持续存在。

As we describe next, theoretically motivated analyses of population activity data have firmly established that low-dimensional attractor dynamics are ubiquitous in the brain, across levels in the brain’s hierarchy and across species.

正如我们接下来描述的那样, 对群体活动数据的理论动机分析已经牢固地确立了低维吸引子动力学在大脑中无处不在, 跨越大脑层次结构的各个层次和物种.

Discrete attractors

Up and down states.

The simplest example of non-trivial discrete attractor dynamics (that is, beyond a single point attractor) is bistability.

Bistable dynamics are a feature of cortical activity in the form of up and down states, in which the subthreshold membrane potential of neurons switches between a hyperpolarized state and a relatively depolarized one, with long persistence (in the order of hundreds of milliseconds to seconds) per state (Fig. 3a).

The two states are relatively invariant over time, as seen in the relatively sharply peaked histograms (Fig. 3a), and despite presumed internal noise in the system the peaks are well separated, suggesting relatively rapid corrective dynamics towards the two states.

There is little evidence of a strong contribution from cellular bistability in supporting these states, suggesting that it is a network-driven phenomenon involving self-excitation and global inhibition. Transitions are believed to be driven through adaptation (from up to down) and by stochastic as well as external coordinating events (from down to up).

Although these states and switches can occur in the cortex without input from the thalamus and striatum, they tend to be synchronous across the cortex and striatum. Thus, the origin of up and down states may be highly distributed.

非平凡离散吸引子动力学 (即超出单点吸引子) 的最简单例子是 双稳态.

双稳态动力学是 皮层活动 的一个特征, 表现为上升和下降状态, 其中神经元的亚阈值膜电位在 超极化 状态和 相对去极化 状态之间切换, 每个状态持续时间较长 (大约数百毫秒到数秒) (图 3a).

down: 超极化, 接近静息状态; up: 去极化, 接近放电阈值, 网络活动强.

这两个状态在时间上相对稳定,从活动分布直方图中的尖锐峰可以看出来 (图3a) 。尽管系统内部存在噪声,这两个峰仍然明显分离,这表明系统具有朝向这两个状态的快速纠正动力学。

目前几乎没有证据表明这些状态是由(单个)细胞层面的双稳态产生的,相反,它们似乎是一个包含 自激活 和 全局抑制 的网络驱动现象。状态转换一般认为是通过适应机制 (从上到下) 以及随机事件和外部协调信号 (从下到上) 触发的。

虽然上/下状态在没有来自丘脑或纹状体的输入时也会在皮层中发生,但它们在皮层和纹状体之间往往是同步的。因此,上/下状态的起源可能是高度分布式的.

Perceptual bistability

Visual and auditory percepts including binocular rivalry, the Necker cube and some auditory illusions offer clear examples of bistability in neural processing, suggesting the operation of a dynamical system with two attractors.

In these illusions, the brain (at the level of perceptual reports) selects one possible interpretation of an ambiguous input, often switching between possibilities. Although the phenomenon has long been known and studied, no localized bistable attractor circuit has been identified as the basis of perceptual bistability.

Indeed, some percepts may involve top-down activation and modulation of activity across many brain areas, suggesting once again a widely distributed circuit for bistability.

视觉和听觉知觉, 包括 双眼竞争、Necker 立方体和一些 幻听错觉, 提供了神经处理中的双稳态的清晰例子, 表明具有两个吸引子的动力系统的运行.

双眼竞争: 两只眼输入不同图像, 一次只能意识到其中一幅

Necker 立方体: 一种二维图像, 可被知觉为两种不同的三维立方体视角

在这些错觉中, 大脑 (在感知报告的层面上) 选择对模糊输入的一种可能解释, 通常在可能性之间切换. 尽管这一现象早已为人所知并被研究, 但尚未确定任何局部双稳态吸引子回路作为感知双稳态的基础.

事实上, 一些知觉可能涉及对跨脑区的自上而下的激活和活动调制, 再次暗示双稳态可能由一个 高度分布式 的回路产生.

Bistability in a premotor area

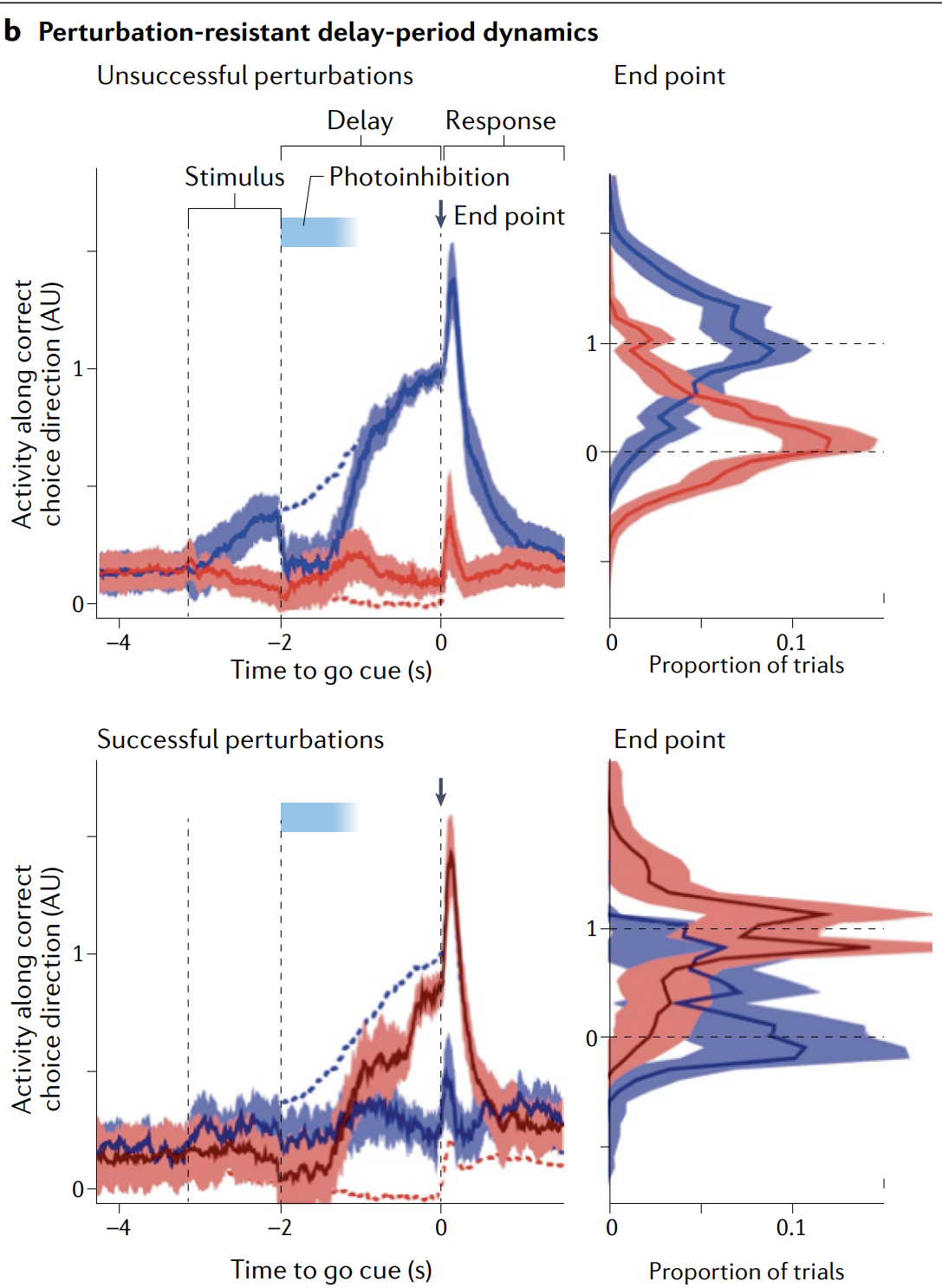

Recent studies identify and localize discrete attractor dynamics in a mouse premotor area, the anterior lateral motor cortex (ALM).

In a cued two-alternative delayed response task, ALM neurons exhibit persistent activity over a 1-s delay period.

During the post-cue delay period, activity evolves towards one of two states that guide the response (Fig. 3b), fulfilling the first prediction of attractor dynamics. The delay-period terminal states are similar for cues from different sensory modalities, partially meeting the prediction of invariance.

ALM perturbations during the delay are either erased (corrected) by the circuit (Fig. 3b, top) or drive a jump to the opposite state (Fig. 3b, bottom), which results in the animal making the wrong action, suggesting bistable switching dynamics similar to the mechanism shown in either Fig. 1b or Fig. 2e.

最近的研究在小鼠的前运动区域——前外侧运动皮层 (ALM) 中识别出并定位了离散吸引子动力学。

在一个由提示引导的二选一延迟反应任务中,ALM 神经元在约 1 秒的延迟期内表现出持续活动。

在提示之后的延迟阶段,活动会向两个状态之一演化,而这两个状态将引导动物的行为反应 (图 3b) ,满足了吸引子动力学的第一个预测。

强持续活动; 逐渐分化为左/右吸引子; 状态一旦接近吸引子就被吸引稳定.

对于来自不同感官模态的线索,延迟期的终末状态彼此相似,从而部分满足了吸引子动力学关于“不变性”的预测。

在延迟期间对 ALM 进行扰动时,其影响要么被回路抹除 (纠正) (图 3b 上) ,要么将状态推向另一个吸引子状态 (图 3b 下) ,导致动物做出错误动作,这表明 ALM 中存在类似图 1b 或图 2e 所示机制的双稳态切换动力学。

Given the long training time required for the task and the resulting tailoring of the ALM dynamics to the specific task structure — bistability for a two-choice task — it is likely that this system acquires its dynamics through slow plasticity and, thus, that the network’s recurrent structure is malleable in adult animals. New results showing the existence of small (on the scale of about $100 \mu\text{m}$) clusters of locally recurrent neurons in the ALM that can maintain persistent responses to microstimulation may provide experimental evidence of the theoretically posited mixed modular networks (below) that are hypothesized to support robust and high-capacity memory states.

鉴于该任务所需的长时间训练以及 ALM 动力学对特定任务结构的调整——双稳态用于两种选择任务——该系统很可能通过缓慢的可塑性获得其动力学, 因此网络的递归结构在成年动物中是可塑的. 新的结果显示, 在 ALM 中存在小规模 (约 $100 \mu\text{m}$ 规模) 的局部递归神经元集群, 这些集群可以维持对微刺激的持续反应, 可能为理论上假设的混合模块化网络提供了实验证据, 这些网络被假设支持稳健且高容量的记忆状态.

Discrete multistability

Hopfield networks and WTA networks (which can be viewed as a special type of Hopfield network, with bistable switch networks as a special type of WTA network) are models of multistability beyond bistability.

Hopfield 网络和 WTA 网络 (可以将其视为 Hopfield 网络的一种特殊类型, 双稳态开关网络作为 WTA 网络的一种特殊类型) 是超越双稳态的多稳态模型.

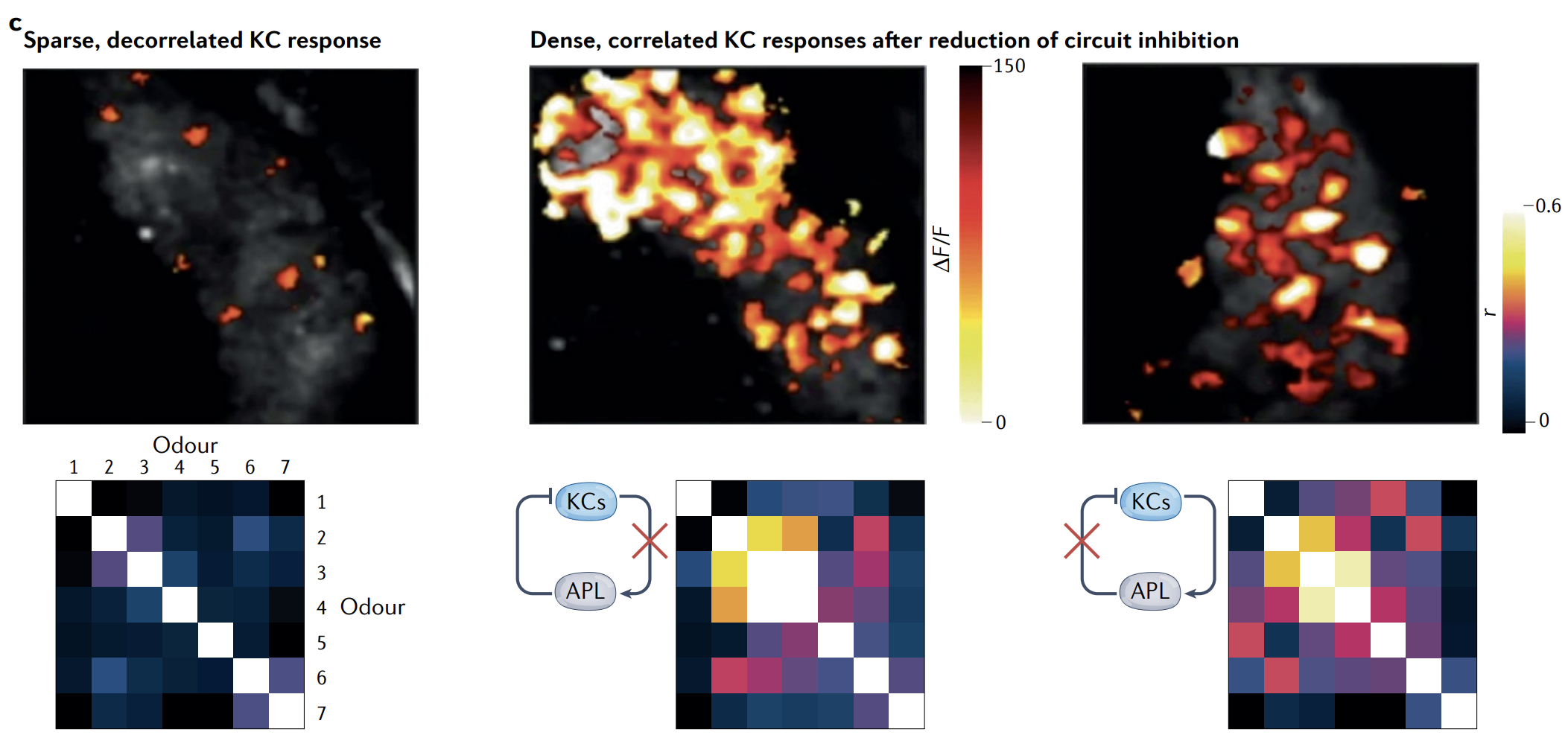

At present, the evidence for discrete multistability as a circuitlevel brain process is less direct and less exhaustive than that for continuous-attractor networks (described below).

However, there are many likely candidate systems and brain regions with dynamics that are suggestive of and consistent with discrete multistability, at least of the special case of WTA attractor dynamics — including in the mammalian hippocampus and auditory cortex, and in the fly and mammalian olfactory system.

In particular, many of these circuits exhibit global inhibition that clearly narrows and refines activity in the circuit (Fig. 3c, left), and also show evidence of selective recurrent excitation that leads to multiple distinct and stably correlated input responses in distinct subpopulations of cells (Fig. 3c, middle and right).

In our view, it is likely that these circuits exhibit multiple discrete attractor states, but quantitative testing of the first three predictions of attractor dynamics and direct demonstration of these states as stable and invariant remain an important future direction for characterizing these circuits.

目前, 作为回路级大脑过程的离散多稳态的证据不如连续吸引子网络 (下面描述的) 直接和详尽.

然而, 有许多可能的候选系统和大脑区域, 其动力学暗示并与离散多稳态一致, 至少是 WTA 吸引子动力学的特殊情况——包括 哺乳动物海马体 和 听觉皮层, 以及果蝇和哺乳动物的嗅觉系统.

特别是, 这些回路中的许多都表现出 全局抑制, 明显缩小和细化了回路中的活动 (图 3c, 左) , 并且还显示出选择性递归兴奋的证据, 导致细胞不同子群中多个不同且稳定相关的输入响应 (图 3c, 中间和右).

在我们看来, 这些回路很可能表现出多个离散吸引子状态, 但对吸引子动力学前三个预测的定量测试以及将这些状态直接证明为稳定且不变仍然是表征这些回路的重要未来方向.

a, Multi-unit activity (MUA) and single-unit activity ($V_{m}$) during cortical up states and down states show signatures of bistability (clusters and histograms at bottom).

a, 皮层 “上态” 和 “下态” 期间的多单元活动 (MUA) 和单元活动(膜电位) ($V_{m}$) 显示出双稳态的特征 (底部的簇和直方图).

b, Delay-period dynamics in rodent premotor area (anterolateral motor cortex (ALM)) during a binary decision task (blue and red correspond to correct and incorrect direction choices, respectively). Before the animal makes a motor report of its decision (at the ‘go’ cue delivery), ALM activity seems to converge to one of two discrete end points (blue and red curves and histograms, top). Perturbations (optogenetic inhibition, denoted by pale blue) are either robustly erased (top; dashed lines show the unperturbed trajectory, and solid line shows a return to the unperturbed trajectory) or flip the dynamics so that the end points are reversed (bottom) and the animal reports the incorrect decision.

b, 在啮齿动物额前运动区 (anterolateral motor cortex,ALM) 执行二选决策任务的等待期 (delay-period) 动力学 (蓝色和红色分别对应正确和错误的方向选择) 。在动物作出运动性报告 (在 “go” 提示之前) ,ALM 活动看起来会收敛到两个离散终点之一 (顶图的蓝色和红色曲线与直方图) 。对网络的扰动 (用光遗传学抑制,图中以淡蓝色表示) 要么被网络稳健地抹去 (顶部;虚线表示未扰动时的轨迹,实线表示扰动后返回到未扰动轨迹) ,要么使动力学翻转,使终点互换 (底部) ,从而动物报告错误的决策。

c, Evidence of all-to-all inhibition and competitive winner-takes-all (WTA) recurrent dynamics in the fly olfactory system. Kenyon cells (KCs) activate anterior paired lateral (APL) inhibitory neurons, which in turn globally inhibit KCs. KC responses to odours, when input from the APL neurons is intact, are sparse: top-left image shows calcium fluorescence responses of KCs to odorant isoamyl acetate. KC responses are also decorrelated across odours (left). Blocking either KC drive to APL neurons or APL inhibition of KCs results in dense and correlated odour responses (middle, right).

c, 在果蝇嗅觉系统中,有证据支持 “全连通抑制 + 竞争性胜者通吃 (WTA) ” 的回馈动力学。Kenyon 细胞 (KCs) 激活前对侧对称的前腹侧抑制性神经元 (anterior paired lateral,APL) ,APL 反过来对所有 KCs 施加全局抑制。当 APL 的抑制通路完整时,KCs 对气味的响应是稀疏的:左上图显示 KCs 对气味异戊醇 (isoamyl acetate) 的钙荧光响应。KCs 对不同气味之间的响应也被去相关 (左) 。阻断 KC 驱动 APL 或阻断 APL 对 KCs 的抑制都会导致对气味的响应变得密集且高度相关 (中、右图) 。

若系统是真双稳态,数据会聚成两簇 (上态簇、下态簇) ,对应下图中 “聚类” 和 “直方图” 的双峰形态。

Continuous attractors

The oculomotor integrator

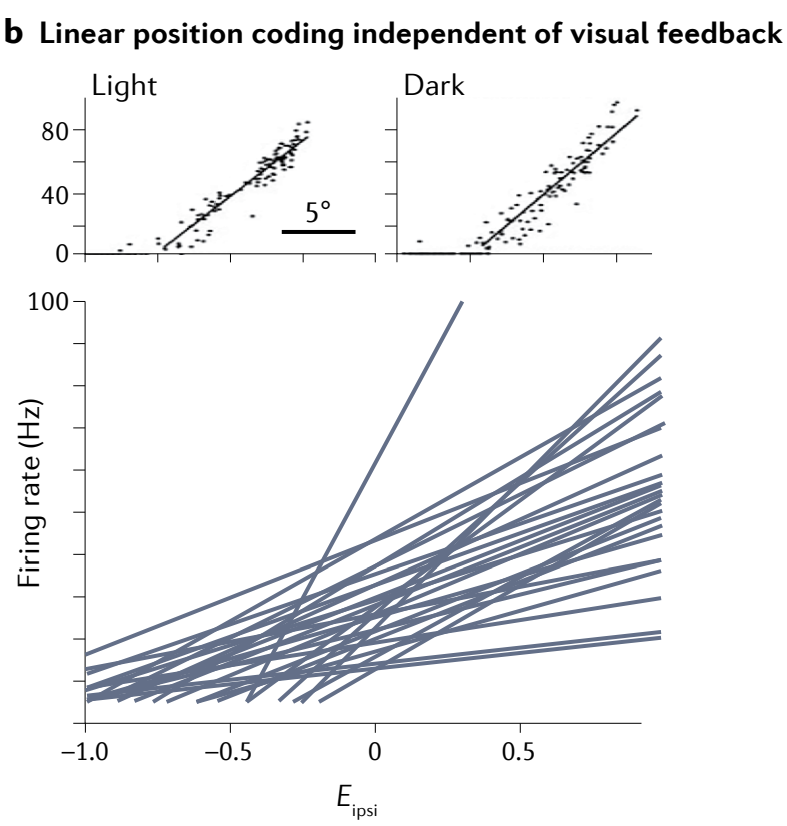

The oculomotor integrator, together with the head-direction circuit, was one of the first systems in neuroscience to be studied theoretically and experimentally as a continuous-attractor network — specifically as a line attractor (Fig. 1e). This network, which is presynaptic to the motor neurons that control horizontal eye position, is highly conserved across vertebrates, from fish to primates.

It integrates pulse-like saccadic eye movement-command signals to generate step-like stable muscle tension command signals (Fig. 4a) that persist autonomously at graded activity levels after removal of the movement cue and even in the dark in the absence of visual feedback (Fig. 4b; third prediction), and thus enable stable gaze fixation at various degrees of eccentricity. Saccadic inputs knock the system slightly off the linear response states, but the neural responses rapidly decay back towards the persistent firing states (in line with the second prediction). Remarkably, the same system also integrates smooth head-velocity signals to permit gaze stabilization during head movement.

眼动积分器 与 头朝向回路 一起, 是神经科学中最早作为连续吸引子网络进行理论和实验研究的系统之一——尤其是线性吸引子 (图 1e). 该网络位于控制水平眼位的运动神经元的前突触处, 在从鱼类到灵长类动物的脊椎动物中高度保守.

它积分脉冲状的扫视眼动指令信号, 以生成阶梯状稳定的肌肉张力指令信号 (图 4a) , 在去除运动提示后甚至在黑暗中没有视觉反馈的情况下以分级活动水平自主持续存在 (图 4b; 第三个预测) , 从而实现各种 偏心度 的稳定凝视固定. 扫视输入会使系统略微偏离线性响应状态, 但神经响应会迅速衰减回持续发射状态 (符合第二个预测). 值得注意的是, 同一系统还积分平滑的头部速度信号, 以允许在头部运动期间稳定凝视.

a, In the goldfish, the positions of the ipsilateral and contralateral eyes ($E_{\text{ipsi}}$ and $E_{\text{contra}}$, respectively) can be maintained for a stable horizontal gaze during inter-saccadic fixation at different angular positions (top two traces). This is supported by stable steps in firing rate by oculomotor integrator neurons (bottom two traces show extracellularly recorded firing rate and voltage (V)), which integrate transient (in the order of about 100 ms) saccadic command bursts.

a, 在金鱼中, 双侧眼睛的位置 (分别为同侧眼 $E_{\text{ipsi}}$ 和对侧眼 $E_{\text{contra}}$) 可以在不同角度位置的扫视间固定期间保持稳定的水平凝视 (顶部两条曲线). 这得益于眼动积分器神经元的稳定阶跃发射率 (底部两条曲线显示细胞外记录的发射率和电压 (V)) , 它们积分瞬时 (大约 100 毫秒) 扫视指令爆发.

b, Oculomotor neurons drive eye position with linearly ramping tuning curves (bottom). Their responses are the same in the light and the dark (top), and thus do not depend on visual input for gaze stabilization on the timescale of seconds.

b, 眼动神经元通过线性斜坡调制曲线驱动眼位 (底部). 它们的响应在光照和黑暗中是相同的 (顶部) , 因此在数秒的时间尺度上不依赖于视觉输入来稳定凝视.

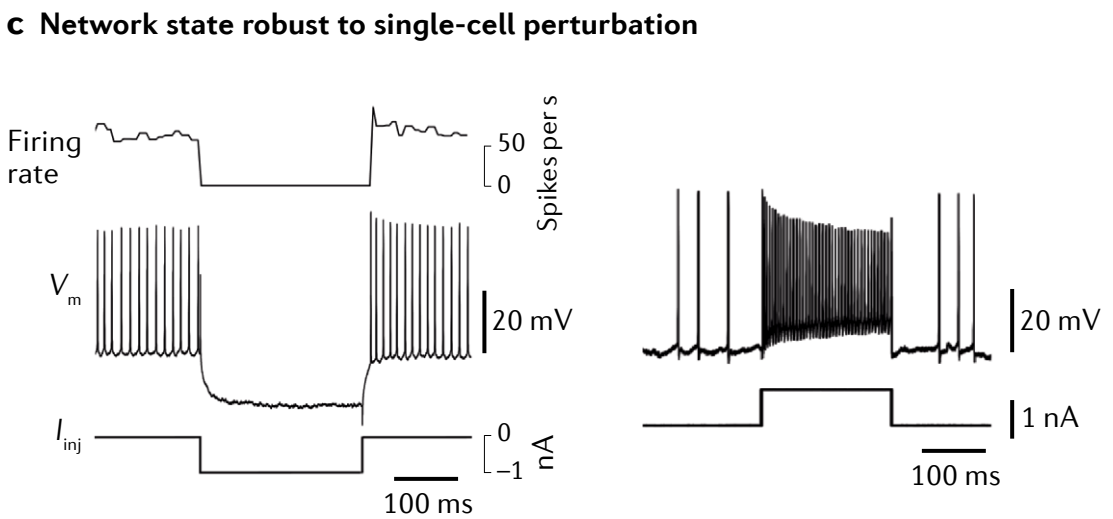

c, Transient current injection into individual oculomotor neurons results in only a transient (that is, not persistent)** decrease (left)** or increase (right) in firing rate, consistent with lack of a cellular origin for persistent intersaccadic firing.

c, 对单个眼动神经元进行瞬时电流注入仅导致发射率的瞬时 (即非持续)** 降低 (左)** 或 增加 (右) , 这与持续扫视间发射缺乏细胞来源一致.

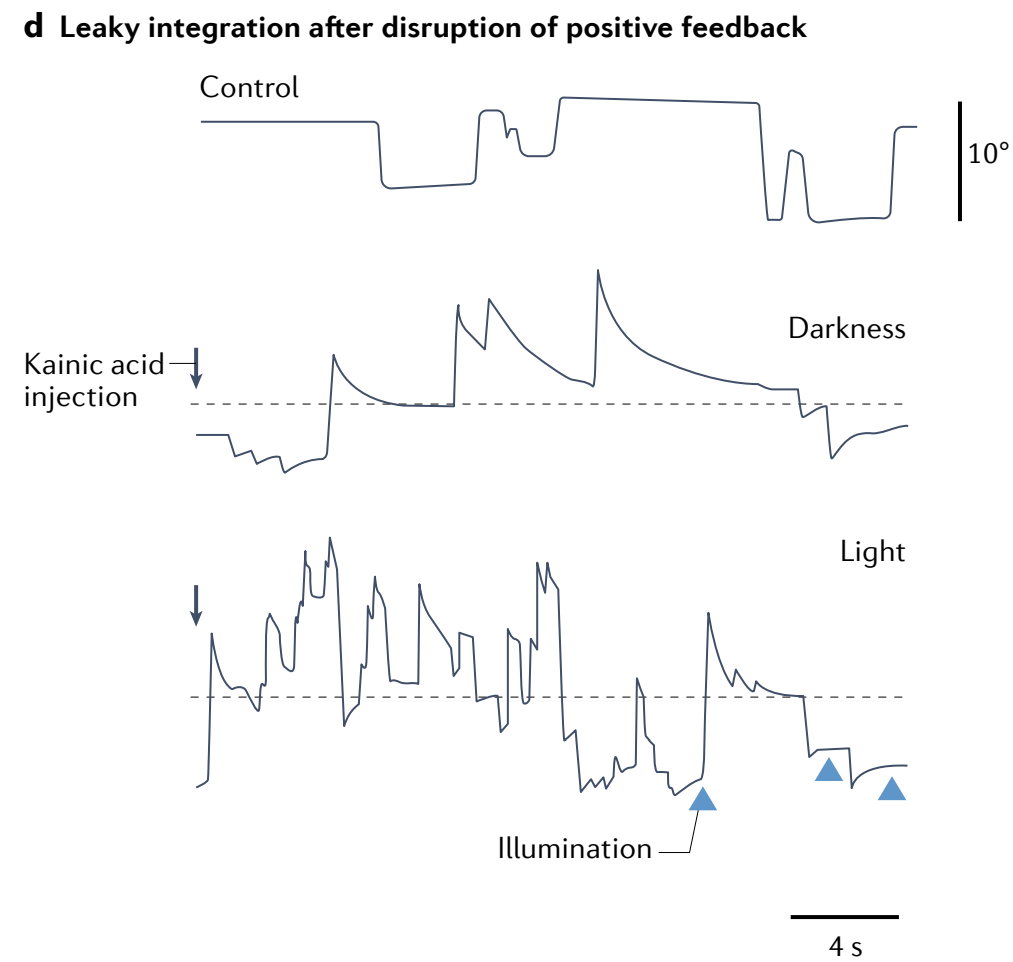

d, Injection of kainic acid into the oculomotor integrator produces leaky dynamics in horizontal eye position, consistent with network models. The leak is pronounced in the dark and is still present although reduced, presumably because of visual feedback, during illumination (triangles).

d, 向眼动积分器注入 kainic acid 会在水平眼位中产生泄漏动力学, 这与网络模型一致. 泄漏在黑暗中尤为明显, 在光照期间 (用三角形表示) 虽然有所减少但仍然存在, 这可能是由于视觉反馈的缘故.

理想的积分器应该使得眼睛位置保持稳定. 而不完美的积分器会使得眼睛指数衰减回中心:

$$ \dot{x} = -\frac{1}{\tau} x\Rightarrow x(t) = x(0) e^{-t/\tau} $$

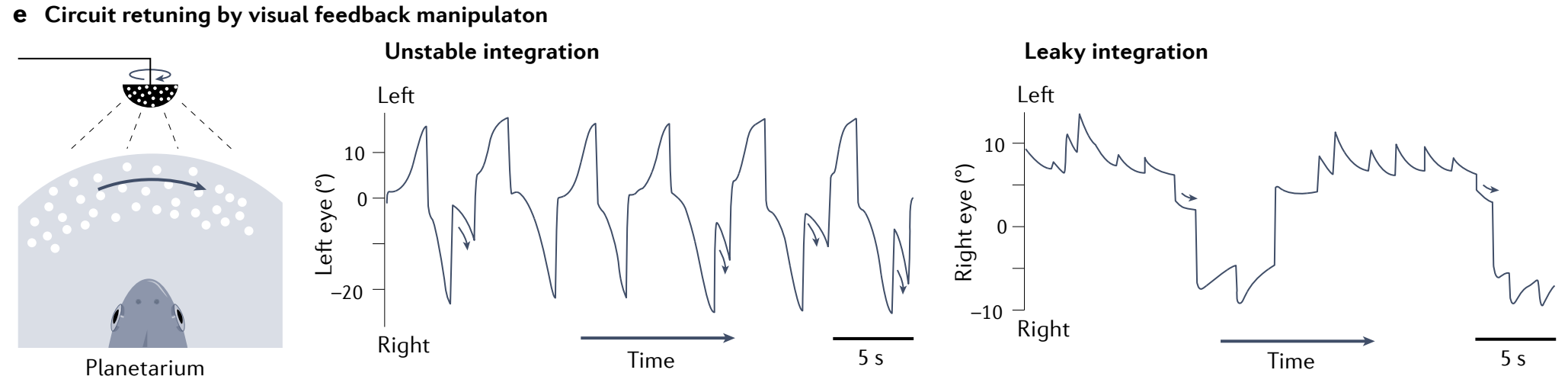

e, Visual training (here, from the motion of dots of light in a planetarium-like set-up) that mimics leaky or unstable eye positions in goldfish can mistune the oculomotor integrator, making it unstable or leaky, respectively. Arrows highlight fixations following saccades towards the mid position.

e, 模拟金鱼中泄漏或不稳定眼位的视觉训练 (这里是通过在类似天文馆的设置中点光源的运动) 可以使眼动积分器失调, 分别使其变得不稳定或泄漏. 箭头突出显示了扫视向中间位置后的凝视.

Integration functionality is a network-level rather than single-cell process: single neurons do not generate persistent responses to transient current injections (Fig. 4c, inset), whereas decreasing network feedback through the use of synaptic blockers reduces the time constant of integration and results in a leaky integrator (Fig. 4c).

It is possible to reduce or increase network feedback through training with a virtual surround that generates an artificial retinal-slip percept (Fig. 4d), implying that the system is capable of error-driven fine-tuning to maintain a high degree of persistence144.

Finally, a recent electron microscopy reconstruction finds recurrent synaptic interconnectivity between integrator neurons, with excitatory connections between ipsilateral neurons and primarily inhibitory contralateral projections, in excellent agreement with line-attractor models of the oculomotor circuit (Fig. 1e).

积分功能是网络级而非单细胞过程: 单个神经元对瞬时电流输入不会产生持续响应 (图 4c, 插图) , 而通过使用突触阻断剂减少网络反馈会降低积分的时间常数, 并导致泄漏积分器 (图 4c).

通过使用产生人工视网膜滑动知觉的虚拟环境进行训练, 可以减少或增加网络反馈 (图 4d) , 这意味着该系统能够进行误差驱动的微调以保持高度的持续性.

最后, 最近的一项电子显微镜重建发现了积分器神经元之间的递归突触互连, 同侧神经元之间存在兴奋性连接, 而主要是对侧投射抑制, 这与眼动回路的线性吸引子模型非常吻合 (图 1e).

Head-direction cells

Some of the earliest experiments to suggest the existence of low-dimensional continuous-attractor dynamics were done in the rodent head-direction circuit (Fig. 5a,b).

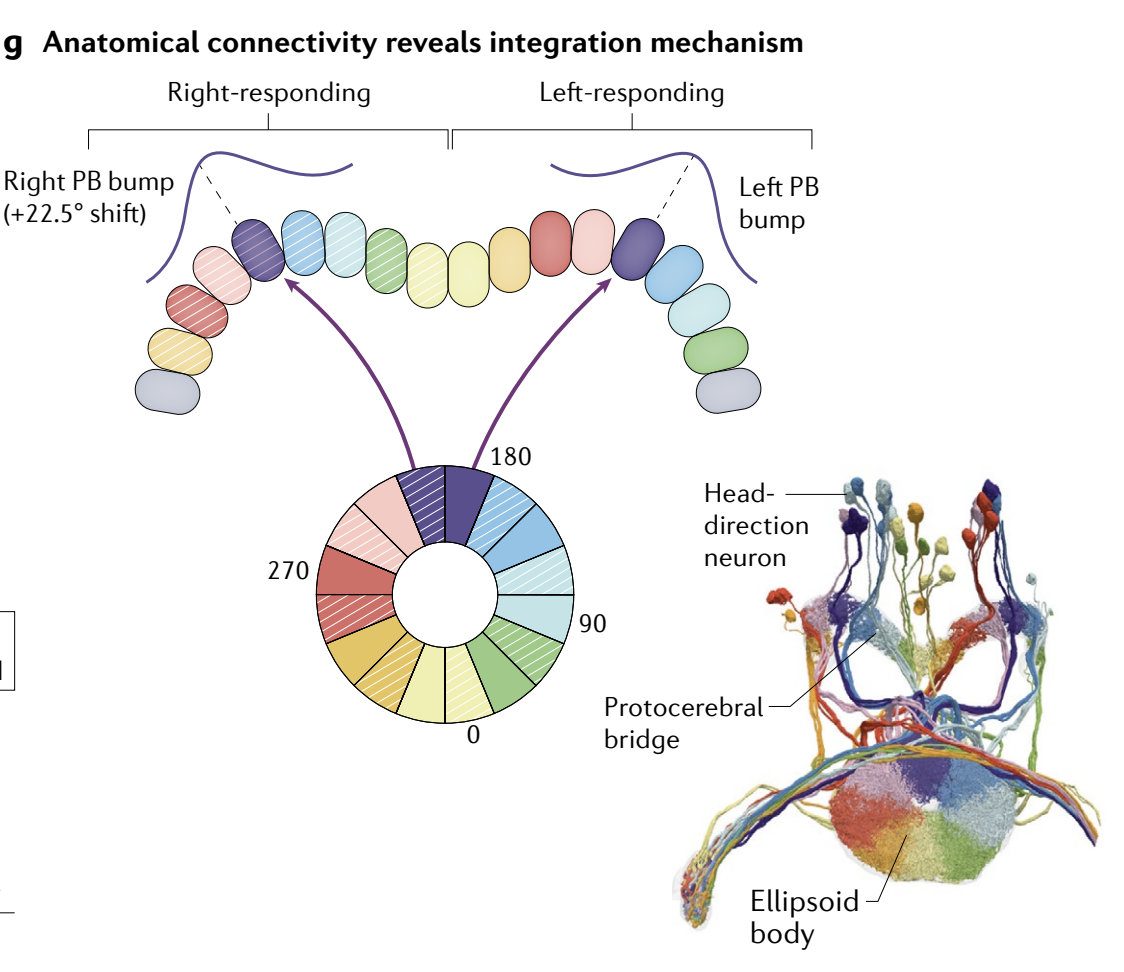

The headdirection circuit in mammals maintains an updated internal compass estimate of the heading direction, relative to some arbitrary external reference, as animals move around. It does so by integrating internal rotational velocity estimates during navigation and incorporating information from external cues. The head-direction circuit is modelled as a ring-attractor network (Fig. 1c,g, left).

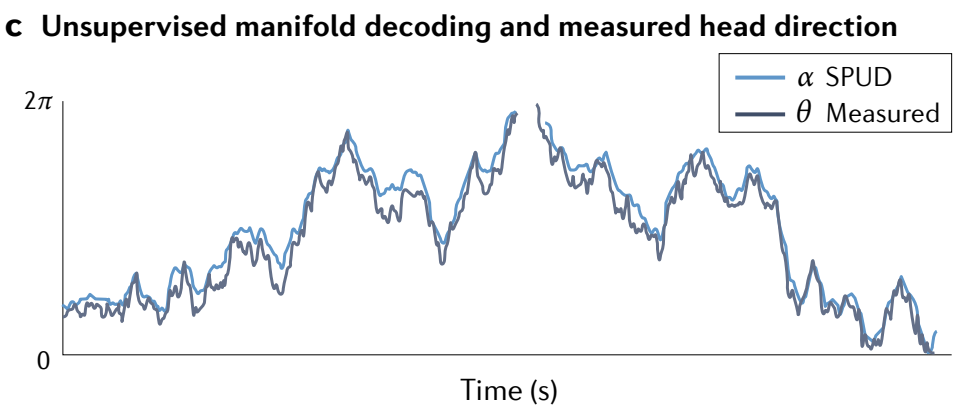

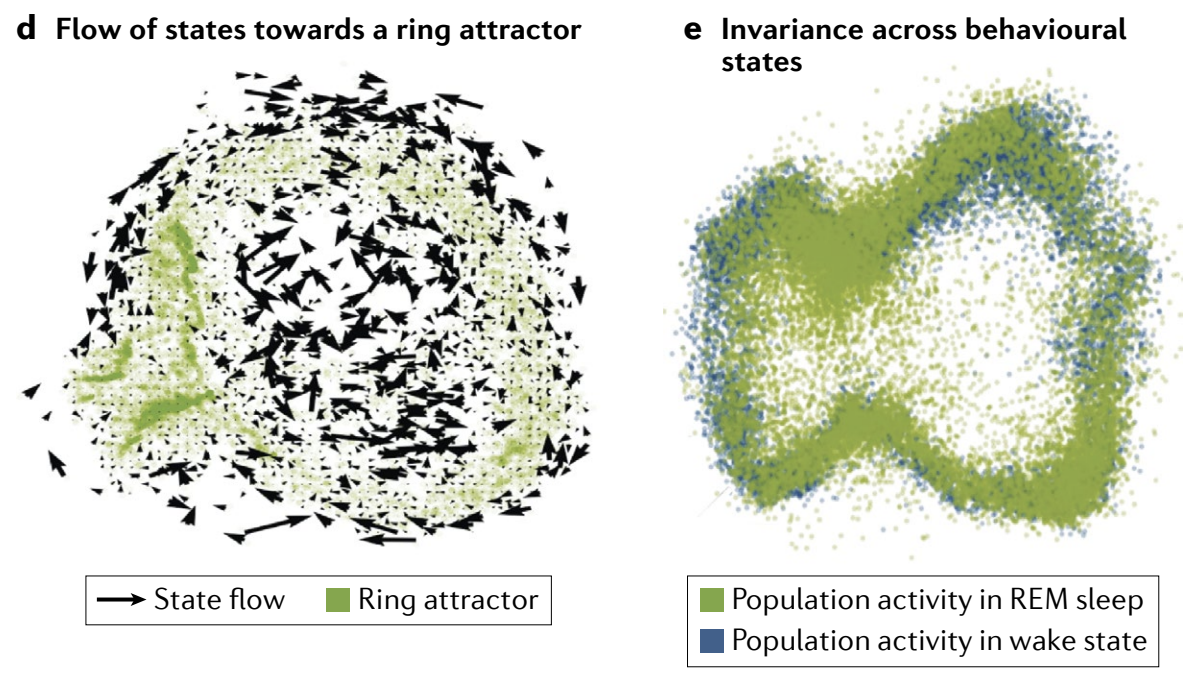

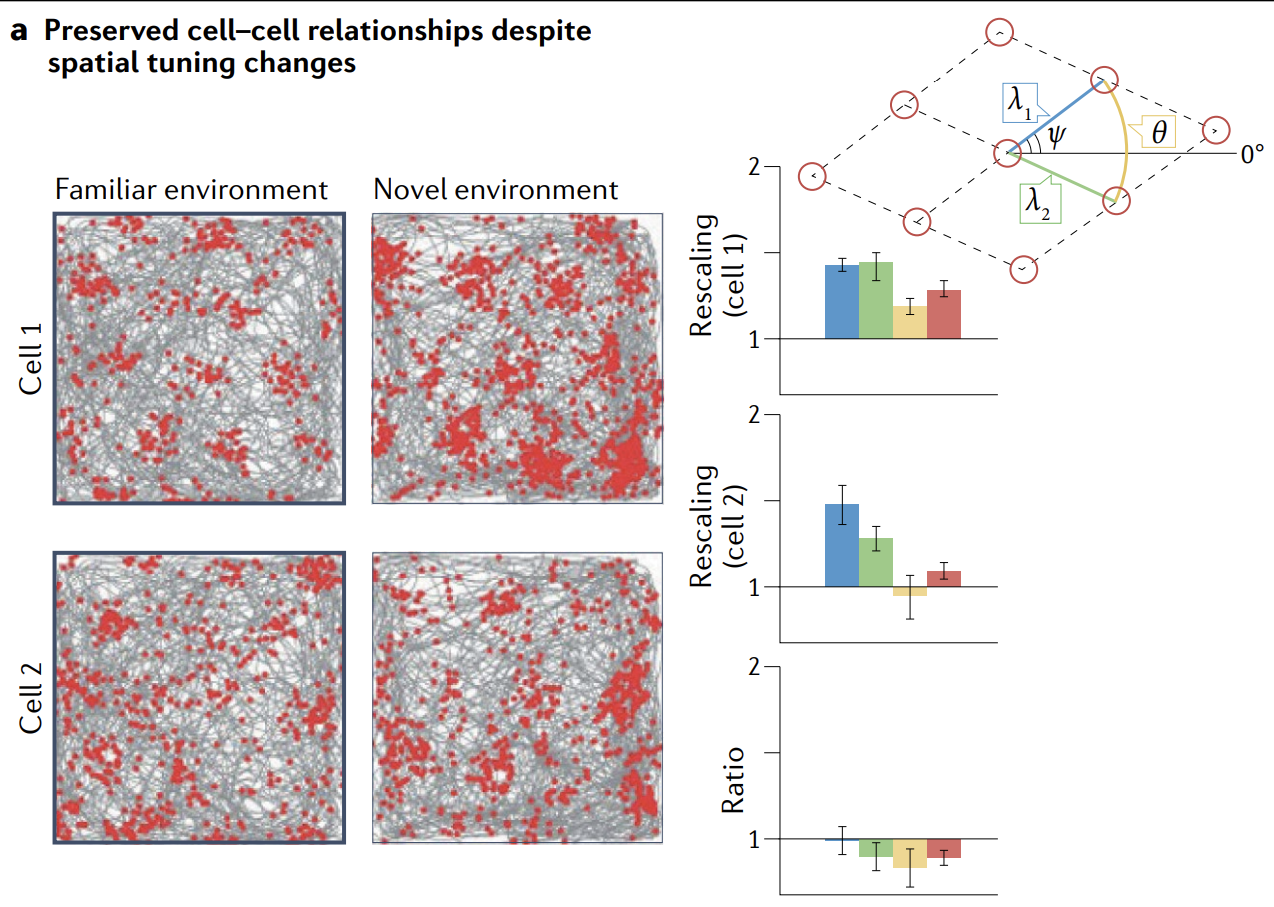

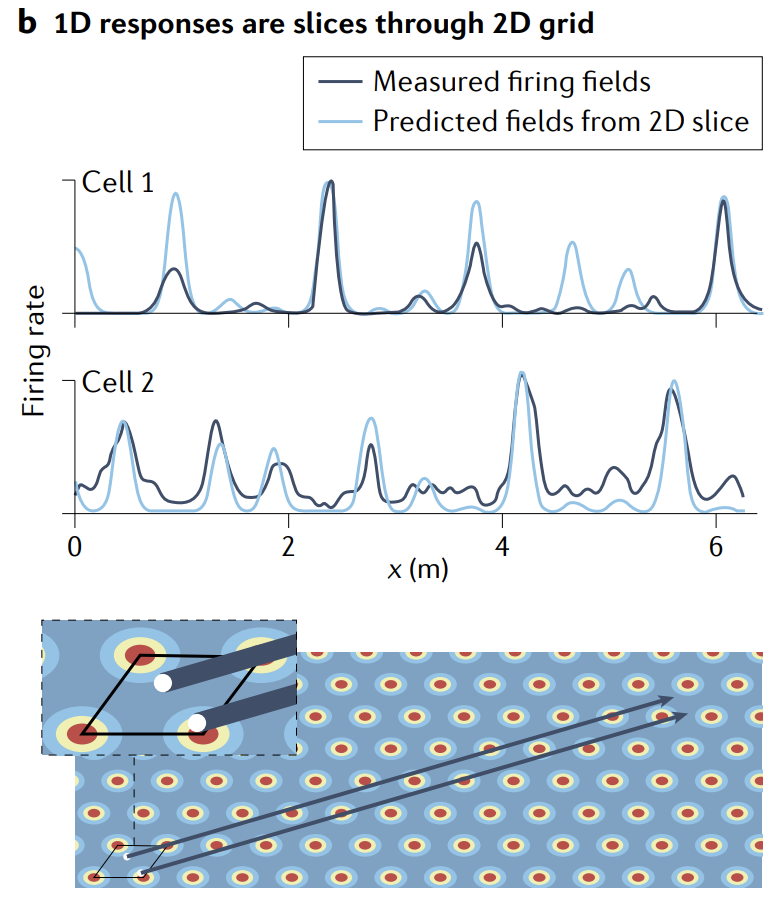

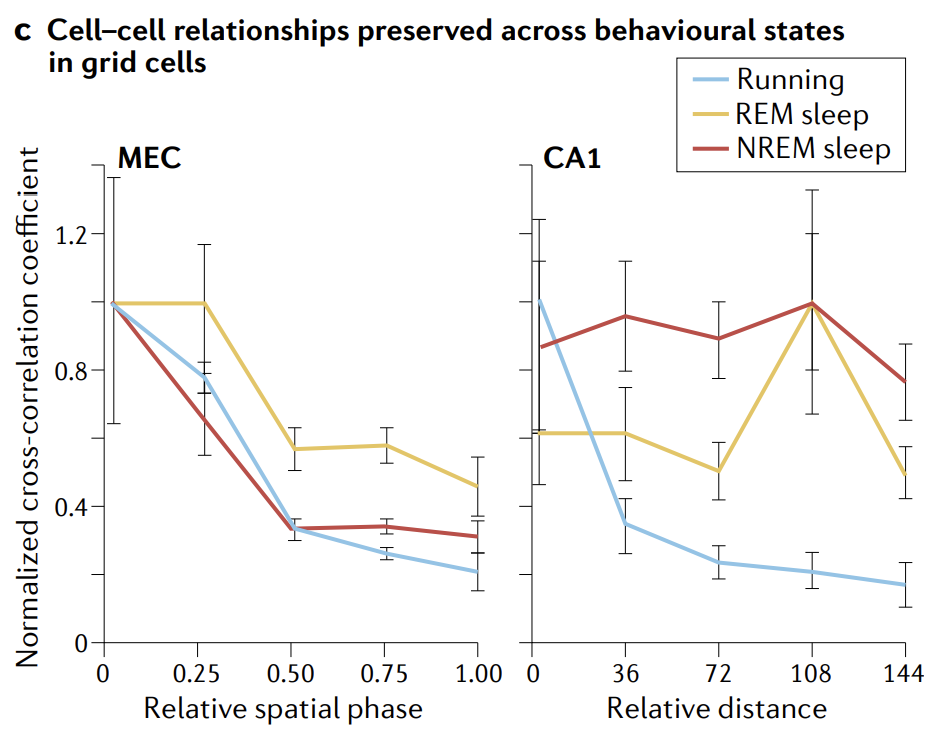

Before large population recordings became available, cell-cell correlations established that the network states remained invariant on a very lowdimensional manifold across environments (Fig. 5a), in line with the first and third predictions. The complete set of states of the several thousand-neuron mammalian head-direction network was shown to consist solely of a one-dimensional ring (Fig. 5b) (in line with the first prediction), revealing that the brain has completely factorized its navigational representations to dedicate a circuit only to head direction.

Furthermore, intervals in the state-space ring manifold map isometrically to intervals of head direction (in line with the fourth prediction), as evidenced by a close match between the isometrically parameterized internal ring states and the measured head direction (Fig. 5b, inset and right).

最早的一些表明存在低维连续吸引子动力学的实验是在 啮齿动物 头部方向回路中完成的 (图 5a, b).

哺乳动物的头部方向回路在动物四处移动时, 保持相对于某个任意外部参考的航向方向的更新内部指南针估计. 它通过在导航过程中积分内部旋转速度估计并结合来自外部线索的信息来实现这一点. 头部方向回路被建模为环形吸引子网络 (图 1c, g, 左).

在大规模集群记录实现前, 细胞-细胞相关性确定了网络状态在非常低维流形上在不同环境中保持不变 (图 5a) , 符合第一个和第三个预测. 哺乳动物头部方向网络的几千个神经元的完整状态集被证明仅由一维环组成 (图 5b) (符合第一个预测) , 揭示了大脑已经完全分解了其导航表示, 以专门用于头部方向的回路.

此外, 状态空间环流形中的间隔与头部方向的间隔等距映射 (符合第四个预测) , 这可以通过内环状态与测量的头部方向之间的密切匹配来证明 (图 5b, 插图和右侧).

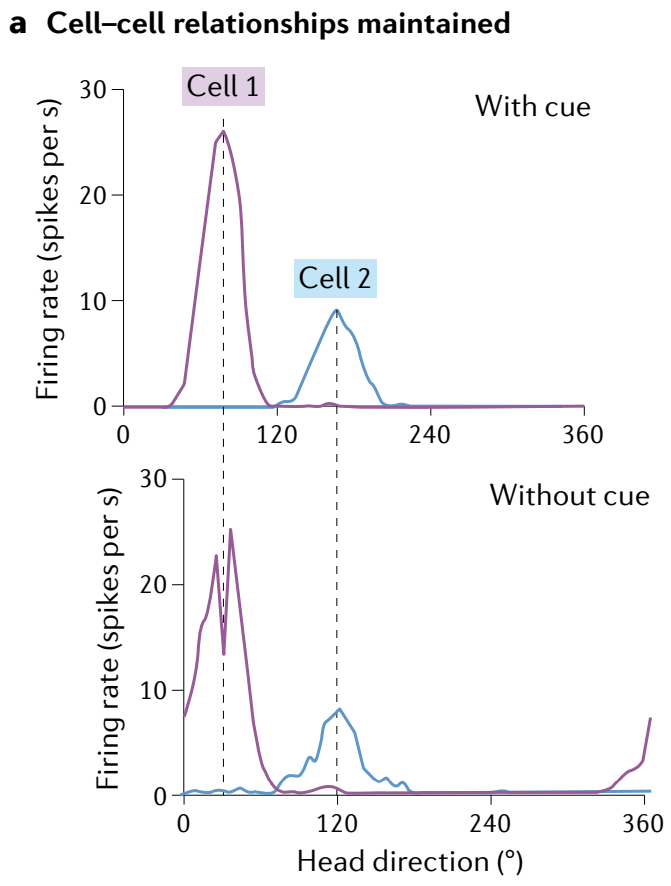

a, Activity of two cells in the rat head-direction circuit during free foraging in a two-dimensional circular arena with a globally orienting cue (top). When the cue is removed (bottom), the fields rotate, but the cells maintain their tuning shapes and relative tuning angles (pale curves show the cells’ activity from the top plot, but globally rotated).

a, 大鼠头部方向回路中两个细胞在带有全局定向提示的二维圆台中自由觅食时的活动 (顶部). 当提示被移除时 (底部) , 细胞的调制场会旋转, 但细胞保持其调制形状和相对调制角度 (淡色曲线显示顶部图中的细胞活动, 但进行了全局旋转).

b, The population-level states of the anterodorsal thalamus during free-foraging and other natural behaviour in a two-dimensional environment, shown through nonlinear embedding in two dimensions and independently validated by topological data analysis, are confined to a onedimensional ring (as in Fig. 1c). Inset: another view of the same ring manifold in three dimensions (left). The manifold is colourized based on a computational approach called SPUD (spline parameterization for unsupervised decoding): the manifold is fit by a spline of matching dimension and topology (middle), and the spline is parameterized isometrically; equal changes in parameter value for equal distances along the manifold (right). Parameter changes are indicated by colour.

b, 在二维环境中自由觅食和其他自然行为期间, 前背丘脑的集群水平状态通过二维非线性嵌入显示,并通过拓扑数据分析独立验证,限制在一维环上 (如图 1c 所示). 插图: 三维中同一环流形的另一种视图 (左). 流形基于一种称为 SPUD (无监督解码的样条参数化) 的计算方法进行着色: 流形由具有匹配维度和拓扑的样条拟合 (中间) , 并且样条是等距参数化的; 流形上相等距离的参数值变化相等 (右). 参数变化由颜色表示.